A Historic Day On Deck: Powell Hikes, Putin Defaults

Tomorrow we get the highlight of what has already been an event-packed week, when at 2pm the Fed will hike rates for the first time since December 2018, raising the Fed Funds rate from 0% where it has been since the covid crisis to 0.25%. The widely telegraphed rate hike will be the first of many as the Fed scrambles to contain inflation which has led to a record high, double digit PPI and the highest CPI since the early 1980s, when the Volcker Fed hiked rates as high as 20% to contain galloping inflation. And, in doing so, the Fed will also set the US economy on course for a crash landing, with forward OIS market already pricing in almost 2 rate cuts over the next three years, a number that will only grow as the US slides into a crippling recession over the next few quarters (we will have a full FOMC preview later today).

Also tomorrow, another even more momentous event may take place when Russia is due to make two interest payments on its dollar bonds on Wednesday, but it is unclear whether western investors will actually receive their cash in dollars, in devalued rubles, or at all, potentially lining up a uniquely messy government debt default, the first since 1998 which eventually led to the collapse of LTCM and the start of the too big to fail bailout culture which defines the US financial system to this day.

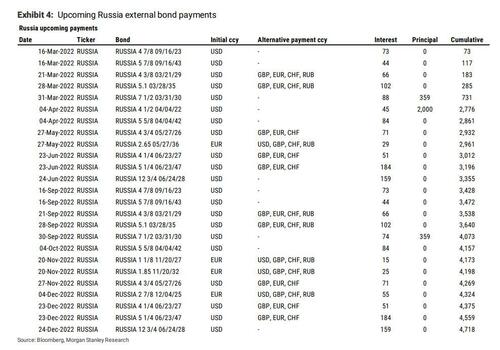

On Wednesday, March 16, Russia is scheduled to hand investors a total of $117 million in interest payments on two of its bonds: namely $73 million on RUSSIA USD 2023 and $44 million on RUSSIA USD 2043. There is a 30-day grace period on these bonds, meaning that there may be time until April 15 to pay it; if it does not, that would constitute a default. There is no alternative payment clause on these bonds.

The next principal payment is on March 31, $359 million on RUSSIA USD 2030, which has a 15-day grace period, which again brings it to April 15. This is then followed by a $2 billion principal payment from RUSSIA USD 2022 maturing on April 4. Many more scheduled payments follow until the end of the year.

Altogether Russia has some $38.5BN of foreign-currency bonds (a tiny amount: the US issues roughly this much in every single monthly 10Y auction), of which roughly $20BN are owned by overseas investors. But foreigners also hold roughly 20% of Moscow’s local currency debt, which totaled roughly $200bn before the war sparked a collapse in the value of the ruble and made the bonds virtually untradeable.

The Russian government has already said that a recent coupon payment on these local bonds would not reach foreign holders, citing a central bank ban on sending foreign currency abroad. This has already been painful for western asset management groups. More than two dozen have had to freeze funds with significant Russia exposure, while others have sharply written down the value of their Russian holdings.

Will Moscow pay? As the FT notes, the finance ministry said on Monday that it had ordered the payments to be made as usual, but added that its ability to do so could be curbed by western sanctions against the Russian central bank. Finance minister Anton Siluanov said those sanctions – brought in earlier this month – were bouncing the country into an “artificial default”.

Digging deeper, there are both external and internal constraints that may limit payment.

In terms of the former, it may be that the US will prohibit payments being made on Russia’s eurobonds. This issue appeared with Directive 4 under Executive Order 14024 that prohibits US persons from conducting certain transactions with Russia’s Ministry of Finance. While it is unclear whether this extends to US banks receiving coupon payments, General License 9A appears to clarify that it would. In particular, it notes that prohibitions from Directive 4 related to the receipt of interest and maturity payments relating to debt or equity of specified entities issued before February 24, 2022 would be authorized only through May 25,2022.FAQ 981 then also notes that, beyond this date,a specific license would be required to keep receiving these payments. This all suggests that beyond May 25, it would not be possible for NYC banks to receive the interest payments, and that banks would need to ‘reject’ such transactions. This would therefore impact the interest payments due on May 27 for RUSSIA USD 2026 and EUR 2036.

Alternatively, a key domestic constraint to payment is that there may simply no longer be a willingness by Russia to make payments given the tough sanctions applied at this stage, especially given that making these payments would require using up FX that may increasingly be in short supply. Announcing that Russia is not allowing domestic bond OFZ repayments to be taken outside Russia already makes this point. Separately, a decree has now also been published by the Kremlin (see here) that allows for the repayment of foreign debt to select non-residents to be made to onshore accounts in RUB as opposed to being made to foreign accounts in FX. The decree states that this is applicable to both the government and other entities. For now, it’s not clear whether it is mandatory, or whether the CBR/Ministry of Finance would be willing to use their apparent override to enable eurobond payments to still go through. However, given that similar restrictions have been made for local government bonds, it is certainly possible that it applies to eurobonds too.

According to Morgan Stanley, it is unlikely that Russia will make the foreign debt payments: “we think it is very likely that there will be a missed payment in the coming months, perhaps as soon as the next payment on March 16. There are ways to avoid it. GL9A could be extended once May 25 hits. Also, Russia could decide to make the sovereign debt payments in USD as required. Yet for now this would be far from our base case. Note that as usual a default would not see bonds excluded from the EMBI indices. Index exclusions, barring new rules being put in place given the exceptional circumstances, would only take place due to no secondary trading.”

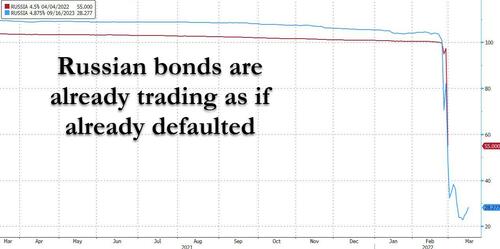

To be sure, markets have already largely priced in a default. Russia’s foreign bonds are trading at about 20 per cent of their face value – a level that suggests very little confidence of being repaid. Credit rating agencies, which up until late February awarded Russia investment-grade status, have slashed it to the very lowest “junk” ratings, with Fitch Ratings saying a default is “imminent.”

If Russia pays in rubles, is it still a default? Siluanov has said it is “absolutely fair” for Russia to make payments on its government debt in rubles until sanctions that he claimed have frozen nearly half of the country’s $643bn in foreign exchange reserves are lifted. But as the FT notes, payment in the Russian currency would still constitute a default in the eyes of most western investors, and not only because of its recent drop in value. Six of Russia’s 15 dollar- or euro-denominated bonds do contain a “fallback” clause allowing repayment in roubles, but the two bonds with coupons due on Wednesday are not among them. Furthermore, late on Tuesday Fitch said that were Russia to make its coupon payments due March 16 in rubles, rather than U.S. dollars, that would constitute a default following the 30-day grace period.

In any case, investors in Europe and the US say sanctions – both their own governments’ and Moscow’s – would in practice make it impossible to set up the Russian bank accounts necessary to receive rouble payments. Lawyers agree with Morgan Stanley (above) and say that even with the loophole of the alternative payment clause, a Russian default is likely and litigation almost inevitable.

What happens next? Typically, a default is followed by a period of negotiation between a government and its bondholders to reach an agreement on restructuring the debt. This is usually done by eventually exchanging the old defaulted bonds with new, less onerous ones, either simply worth less, with lower interest payments or with longer repayment schedules, or a combination of all three. Alternatively, the ECB may just end up buying them to pretend that an event of default never happened although Russia would need to invade Greece for that scenario to work.

While investors are usually reluctant to sue and get a formal default declared by a court because that could make the entire bond come due and potentially trigger defaults in other bonds where payments have not been missed, a “normal” restructuring seems unlikely in Russia’s case. The sanctions are designed to lock the country out of global bond markets and the participation of western investors in any new debt sales is forbidden.

Instead, investors will probably have to sit tight, writing off their Russian bonds and awaiting a de-escalation in the Ukraine conflict that might lead to an easing of sanctions. Some may actually want to quickly vote to demand immediate repayment and get court judgments from US and UK judges that allow them to try to seize overseas Russian assets, to ratchet up pressure on Moscow.

A subset of investors will also be hoping that the failure to make interest payments triggers a payout on credit-default swaps. The decision will be made by a finance industry “determinations committee”, made up of representatives of big banks and asset managers active in the CDS market. Unfortunately, the CDS may not end up helping bondholders, as the financial sanctions could snarl up the intricate system used to settle the contracts and it is unclear just how a CDS auction would take place.

Will a default spark a financial crisis? For a generation of trade, Russia’s last default in 1998 is still a vivid memory. Moscow’s shock decision to devalue the rouble and renege on its local debt followed on the heels of the Asian financial crisis and sent shockwaves through financial markets, leading to the collapse of US hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management, which was bailed out at the behest of the Fed by a consortium of banks, launching America’s too big to fail Wall Street culture.

Even then, Russia kept up payments on its dollar bonds, but defaulted on some Soviet-era international bonds. The last complete external default came in 1918, when the Bolshevik regime repudiated Tsarist-era debts following the Russian Revolution.

Analysts are relatively confident a rerun of 1998 can be avoided. Nikolaos Panigirtzoglou of JPMorgan points out that foreign investors and banks have already been cutting their exposure to Russia since the country’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, unlike the mid-1990s when highly leveraged funds were loading up on Russian assets. So far, the invasion of Ukraine has sparked only modest contagion in other emerging markets, with the far more significant fallout from the crisis being felt in a surge in commodity prices.

Still, anyone predicting that the Russian default won’t have adverse and unexpected consequences, is lying to themselves: as the FT notes, history of finance is littered with examples of how unexpected second-order effects from widely anticipated events still ended up causing broader calamities.

The 30-day grace period means this “probably isn’t yet the moment where we see where the full stresses in the financial system might reside . . . However, this is clearly an important story to watch,” said Jim Reid, a senior strategist at Deutsche Bank.

[ad_2]

Source link