Update on US Dollar as Global Reserve Currency and the Impact of USD Exchange Rates & Inflation

Dollar drops to lowest share in 26 years. Slowly but surely?

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

With inflation raging in the US following the Fed’s $5-trillion money-printing orgy and interest-rate repression, the question constantly arises: When will the rest of the world throw in the towel on the dollar as the dominant global reserve currency? If this were to happen all of a sudden, it would spell chaos. But it is happening little by little.

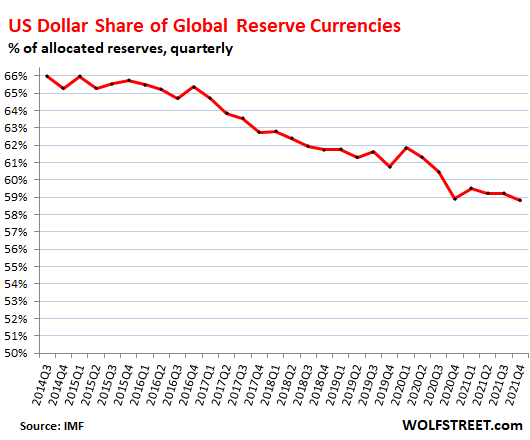

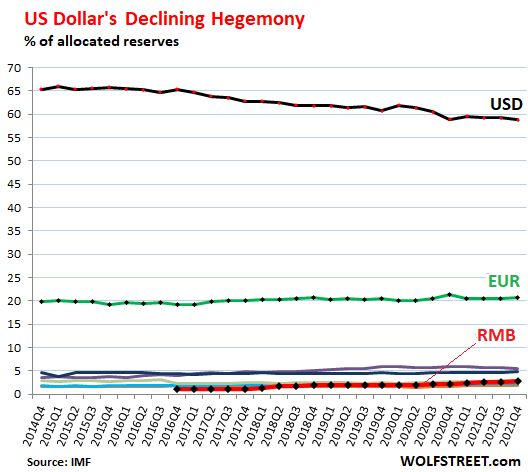

The global share of US-dollar-denominated foreign exchange reserves fell by 40 basis points from Q3 to 58.8% in Q4, setting a new 26-year low, edging out the low in Q4 2020, according to the IMF’s COFER data released at the end of March. Dollar-denominated foreign exchange reserves consist of Treasury securities, US corporate bonds, US mortgage-backed securities, and other USD-denominated assets that are held by foreign central banks and other foreign official institutions.

Over the past 20 years, since 2001 – just before the official arrival of euro banknotes and coins – the dollar’s share has dropped by 12.7 percentage points, from 71.5% then to 58.8% now.

Global foreign exchange reserves do not include the assets held by a central bank in its own currency, such as the Fed’s own holdings of Treasury securities and MBS, the ECB’s holdings of euro-denominated assets, or the Bank of Japan’s holdings of Japanese Government Bonds and other yen-denominated assets.

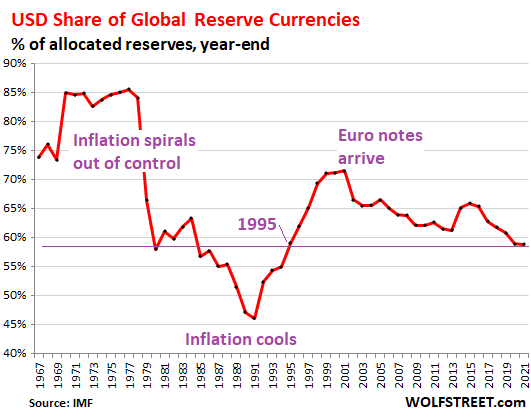

Back in 1977, the prior period when inflation was raging, the dollar’s share was still 85%. But on fears that the Fed would let inflation rage out of control, dollar assets got dumped by central banks, the dollar’s share of global reserve currencies collapsed, hitting bottom a decade after Fed chairman Volcker had started the successful inflation crackdown.

These relationships are slow moving. It took years of inflation before the dollar assets got dumped, and then it took years after inflation was essentially being brought back under control, before dollar-denominated assets were being picked up again.

When the dollar’s share of global reserve currencies drops, the share of other currencies increases, and the dollar becomes less dominant, as other central banks are gradually diversifying away from US dollar holdings (year-end data):

The dollar’s exchange rate v. foreign exchange reserves.

The values of foreign exchange reserves denominated in currencies other than dollars are translated into dollar figures. For example, the value of Japan’s holdings of euro-denominated assets is expressed in dollars at the current EUR-USD exchange rate to make them comparable to other holdings.

But the exchange rate between the USD and other currencies impacts the magnitude of the non-USD assets. In other words, the magnitude of euro-denominated assets held by the Bank of Japan moves with both: a change in euro-assets that the BoJ holds, and the exchange rate of the euro to the dollar.

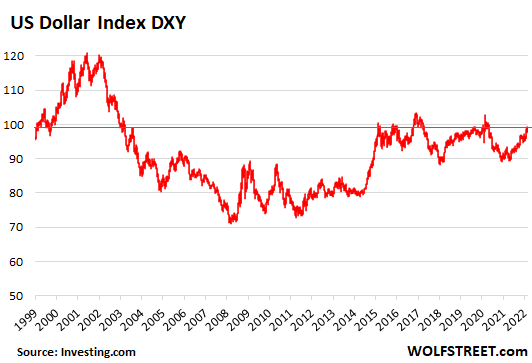

But the exchange rates of the major currency pairs, while volatile from month to month, have been stable over the past 23 years, very well managed, as shown by the Dollar Index (DXY), which tracks the dollar against the euro, yen, British pound, Canadian dollar, Swedish krona, and Swiss franc.

Today, the DXY closed at 98.57, roughly unchanged from its level in 1999 and 2000, despite the dizzying swings in between. Folks who are waiting for the collapse of the dollar, or for the collapse of the euro or the yen for that matter, will have to be very patient.

So over the two decades, on net, the USD exchange rates have had relatively little impact on the US dollar’s share of global reserve currencies. Most of the long-term decline of the dollars share is due to central banks diversifying away from dollar-denominated holdings and into non-dollar holdings, but very slowly and methodically to avoid blowing down this house of cards. But short-term, as we’ll see with the yen in a moment, exchange rates do jostle things around.

Inflation is a different matter.

Inflation tears up the purchasing power of the currency in its own country. And short-term, there is no direct link between inflation and exchange rates. For example, currently the dollar is trading way up against the yen (the yen is dropping against the USD), but the US CPI inflation is the worst among the currencies in the DXY basket, while the inflation rate in Japan, though rising, is still mild.

The euro got stuck.

The Eurozone encompasses 19 countries with a population of 340 million people. When politicians talked up the euro over 20 years ago, they jabbered about “parity” with the dollar as global reserve currency, as trading currency, and as financing currency. And this was progressing until the Euro Debt Crisis put an end to the dream of the euro reaching parity with the dollar as reserve currency.

The euro has gotten stuck in distant second place with a share of around 20% (in Q4, 20.6%). The remaining global reserve currencies have small to minuscule shares:

The minor reserve currencies:

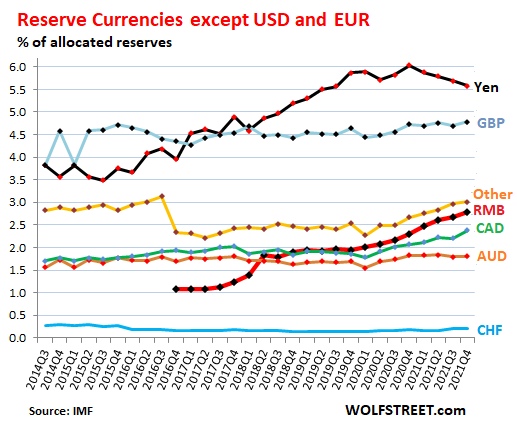

To get a close look at the colorful spaghetti at the bottom of the chart, where the remaining reserve currencies battle for share, I limited the left-hand scale to a range of 0% to 6%. This pushes the dollar and the euro out of the picture.

The share of the yen, the third largest reserve currency, after rising for five years to a share of 6.0% in Q4 2020, started to decline in Q1 2021. By the end of 2021, the yen’s share had fallen by nearly 7%, driven by the exchange rate of the yen against the USD which plunged 10% over the same period. In other words, all of the decline in the yen’s share is explained by the drop in the exchange rate of the yen against the dollar.

The fourth largest reserve currency, the British pound, has held largely level over the past few years, but with a slight upward trend in recent quarters. In Q4, its share of 4.8% was just a tad above its share of Q4 2015.

The Chinese renminbi has been growing fairly consistently in minuscule increments and in Q4 reached a share of a whopping 2.8%, having gained 90 basis points in two years. At this pace, it will take the RMB another 18 years to breach the 10% mark.

The RMB, as the currency of the second-largest economy in the world, should have a larger share. But there are still problems with convertibility. While it’s freely convertible for trade purposes, there are still capital controls in effect.

The importance for the US dollar as top reserve currency.

The US dollar’s role as the dominant global reserve currency has enabled the US to run its gigantic twin-deficits without getting its feathers ruffled: The US government’s incredibly spiking public debt, now over $30 trillion; and the ballooning trade deficit, engineered by Corporate America’s 30-year search of cheap.

Both of these deficits will be harder and more expensive to fund if the dollar gets knocked off its perch.

Of note: The fact that the Eurozone has had a large trade surplus with the rest of the world in recent years – particularly with the US – demonstrates that an economy with a trade surplus can also have one of the top reserve currencies, thereby debunking the outdated theories that the country with a large reserve currency must have a large trade deficit.

But having the dominant reserve currency enables and encourages the US to run up its twin deficits, without much of a price to pay.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? Using ad blockers – I totally get why – but want to support the site? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()

[ad_2]

Source link