The Renewed Politicization of the Federal Reserve

Economic research shows that monetary policy works best when conducted by an independent central bank. After Fed chairs in the 1960s and ‘70s caved to pressure from American Presidents, those who followed sought, at least to some degree, to reestablish the Fed’s independence. Until now, that is.

Since 2019, the Fed has politicized its activities in virtually every way: through its monetary policy goals, the use of its enhanced balance sheet, its regulatory actions, and its emergency lending activities. Each of these changes has pushed the Fed further from being an effective and independent central bank toward becoming a purely political institution, which prevents it from choosing the best policies for Americans and the US economy.

Monetary Policy: “Inclusive” Employment and (Flexible) Average Inflation Targeting

Fed officials, including current Chair Jerome Powell, have acknowledged that monetary policy is a broad tool that cannot be used to address the problems of racial and income inequality. Despite this admission, however, the Fed has injected the issue of inequality into its monetary policy goals.

In August of 2020, the Fed rewrote its statement of goals and strategy to emphasize employment ahead of inflation. The new language described the maximum employment goal as “a broad-based and inclusive goal that is not directly measurable.” Chair Powell cited racial differences in unemployment rates as a motivation for the change. This shifted the Fed’s goal from focusing on the best outcome for most Americans to a purely discretionary target, which the Fed admits is impossible to measure.

At the same time, the new objectives stated that the Fed would target a rate of two percent inflation averaged over time, giving Fed officials greater ability to deviate from the prescribed rate of two percent annual inflation. Moreover, Fed officials have since revealed that they only intend to seek an average two percent when it has previously been below target. When inflation is above target, in contrast, the Fed will allow it to remain so and will not bring it down enough to return to the previous price-level trend.

Taken together, these two changes relax the traditional constraints on the Fed’s ability to engage in overly-expansionary monetary policy. When warned that policy is too loose, they can point to their expanded employment goal to justify the policy. Then, when inflation rises above two percent, they can claim that it is temporary and will not affect the average rate of inflation in the future.

The irony is that such an approach would likely produce exactly the opposite of what is intended. To the extent that emphasizing maximum employment (in the broader sense) and ignoring temporary periods of above-average inflation results in overly-expansionary monetary policy, it risks recessionary corrections and even lower employment than would have occurred had the Fed stuck with its previous policy.

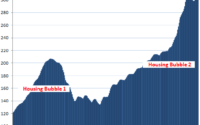

In early 2021, for example, Chairman Powell testified that the Fed planned to keep its interest rate targets near zero until the economy reached maximum employment, a policy it maintained throughout 2021 despite record inflation. Powell now says the US labor market is “unsustainably hot,” but the Fed has taken only minimal action to calm the labor market or bring down inflation. Many commentators are already expressing concerns about a looming recession.

Balance Sheet Activities: Fiscal Accommodation

Through the use of large-scale asset purchases (LSAPs), also known as quantitative easing (QE), the Fed has massively expanded its balance sheet from less than $1 trillion in 2008 to almost $9 trillion today. While the federal government increased fiscal spending by $5 trillion in response to the Coronavirus pandemic, the Fed bought up more than $3.4 trillion in Treasury securities since 2019, effectively monetizing a large portion of the fiscal deficit.

While some economists applauded the Fed’s fiscal accommodation, debt monetization is not a prudent action of a responsible central bank. Those that engage in such activities encourage profligate spending by their fiscal authorities, which often end up in fiscal default. Such massive purchases of Treasury securities were enabled by the Fed’s enlarged balance sheet and would not have been possible in the pre-2008 system.

Emergency lending: Everyone Gets a bailout!

One traditional function of central banks is that they act as emergency lenders in times of financial crises. Although the Fed’s 2008 emergency lending deviated from the rules of the classical lender of last resort, former Fed Chairs Bernanke and Yellen respected the limits of the Fed’s authority as understood by economists and stated in the Federal Reserve Act.

Not so for Jerome Powell. Despite the fact that 2019 was not a case of “unusual and exigent” circumstances in terms of bank failures or shortages of financial liquidity, the Fed initiated a variety of emergency lending facilities beyond those of the 2008 crisis. The Fed lent to non-financial companies and state and local governments, which former Fed chairs said it should never do.

These actions disturb the efficient allocation of capital in the financial system and further heighten the Fed’s political profile.

Regulation: Climate and Industrial Policies

Bank regulators have increasingly used their regulatory powers to discourage banks from supporting politically unpopular industries, such as oil and gas, firearms, and medical marijuana. These punitive measures often take the form of discretionary enforcement actions, which lack the transparency and immutability of rules passed through the regulatory process.

Fed regulators have now turned their sights to climate change and the supposed threat it poses to US banks. The Fed subjects banks to “climate stress tests” and has joined international central banks’ Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), whose stated goal is to “support the transition toward a sustainable economy.” While these changes are ostensibly made in the name of limiting banks’ risk exposure, their result in practice will be to harm the US economy by preventing banks from lending for specific purposes such as the production of energy and fossil fuels.

The Fed’s Politics Threatens Its Independence

Fed officials have gone beyond policy discretion into overt political activism. President of the Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank Neel Kashkari has been reprimanded by Senator Pat Toomey for his recent political actions. In 2020, former New York Fed President Bill Dudley argued that “Fed officials should consider how their decisions will affect the political outcome” by potentially withholding monetary accommodation in order to prevent the re-election of President Donald Trump. Such actions reveal these officials to be political opportunists rather than independent central bankers.

Independent central banks tend to deliver better monetary policy. But independence can only be maintained by focusing on the narrow goals assigned by Congress. By straying from its mandate, Fed officials have chosen to base their decisions on politics rather than on sound economics.

[ad_2]

Source link