Can the Government Even Pay the Rising Interest Expense on its Gigantic Debt as the Fed Pushes up Rates? Yes. Here’s Why

Higher rates eventually enforce a sort of discipline on the drunken party in government and even in the private sector. That would be a good thing.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

There has been a lot of hand-wringing recently among the tightening deniers. They’re now saying, in their latest barrage, that the Fed can never raise its policy rates above x%, such as 2% or whatever, because the government can never pay those higher interest rates on its huge debt and will go bankrupt. And look, they say, interest payments already jumped, and no way that the government can pay much more than that.

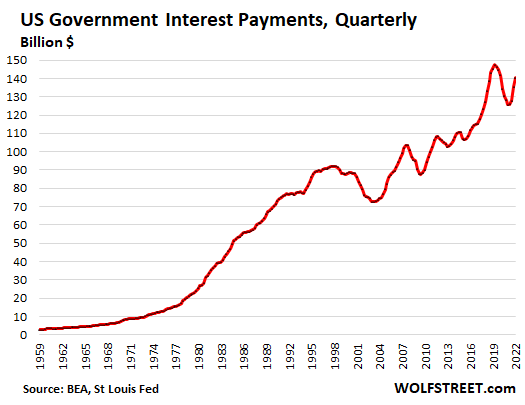

In Q1, federal interest payments on its debt jumped by 11.7% year-over-year to $140 billion. OK, they’re still down a bunch from the peak in Q2 2019 of $147 billion, but you kinda get the idea of what they’re saying:

So let’s take a look.

Only newly issued debt carries the new interest rates. Existing bonds pay the same interest they’ve always paid, until they mature. There are some exceptions, such as Series I Savings Bonds (the I-bonds folks can buy directly from the government), TIPS, floating rate notes, etc. But for most part, Treasury securities pay the interest at which they were issued until they mature. At that point, they’re replaced with new debt, and this new debt comes with the current interest.

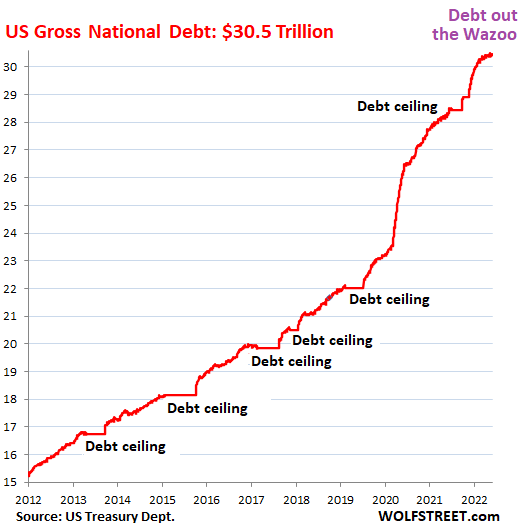

It’s not the $30.5 trillion in total government debt that will suddenly cost more as interest rates rise, but only newly issued debt. So this higher interest expense will spread only gradually over the debt.

Interest expense increased sharply because of the spike in debt. Since March 2020, the gross national debt spiked by $7 trillion, or by 30%, from $23.5 trillion in March to 2020, to $30.5 trillion currently.

The spike in the debt of the Federal government since March 2020 is just stunning. But it slowed in 2022 and is now back to its pre-pandemic growth rate. Obviously, a spike like this cannot be sustained without some major, let’s say, re-arrangement, such as a big bout of inflation, I mean, oops…

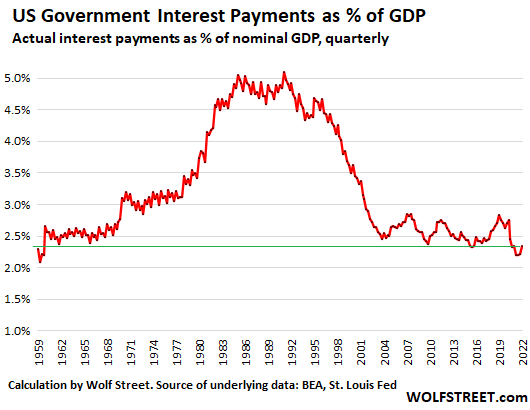

But the burden of interest expense is near historic lows. The government’s tax revenues rise with GDP and with inflation, because growth in economic activity and profits and wage inflation create higher tax revenues, and the Fed’s creature of asset price inflation created higher capital gains tax revenues, though they will go into a tailspin as assets are being repriced under QT and higher rates, and capital gains turn into capital losses.

So interest expense has been rising, but tax revenues have been rising even more quickly along with GDP, and the burden of that interest expense on the US fell to 2.21% of GDP by Q3 2021, the lowest since 1959.

In Q1 2022, interest expense as percent of GDP ticked up to 2.35%, still very near those historic lows. The increase in the percentage was in part due to the decline in GDP in Q1.

In 1985, during the Reagan years, interest payments exceeded 5% of GDP for the first time ever, and they stayed in this 5% range until 1991, when the ratio began to decline, as the lower interest rates were phasing into the debt, and as the economy grew.

For data geeks: The chart is calculated from the actual quarterly interest expense in dollars (not the seasonally adjusted annual rate) divided by quarterly nominal GDP in current dollars (not seasonally adjusted and not inflation adjusted), expressed in percent.

Yield solves all demand problems for debt. Who would want to hold Treasury securities, given this debt and inflation? But here is the thing: If people don’t want to buy 10-year Treasuries at a yield of 3% when inflation is 8%, then yield will have to rise until sellers find a buyer, and at higher yields, the buyers emerge. At some point, a 10-year Treasury paying x% in yield is going to be a great deal, and demand always emerges after some price discovery.

Yield solves those kind of demand problems. And the government will not have any trouble selling new bonds, but they’re going to carry a higher yield – and therefore a higher expense for the government, and higher income for investors.

Higher interest rates enforce discipline. Eventually, higher interest rates combined with ballooning debt levels will push interest expense up to a point where it’s taking more and more of the growing budget, and Congress will have some debates about it, and after some grandstanding and tongue-wagging and taking in the maximum amount of lobbying money, there might even be a compromise on spending and taxes because the only discipline in a capitalist system is the cost of capital.

And if the cost of capital is zero, or is below zero in real terms, and for long enough, then there is no discipline, and the drunken party just keeps going on, and the debt keeps piling up, including in the private sector, until the problem gets solved in another way: Massive inflation, but at a long-lasting and brutal expense to the economy.

Higher interest rates will enforce a sort of discipline on the drunken party, including in the private sector, and will sober up the participants, and prevent the kind of long-lasting destruction that massive inflation wreaks on the economy, and that would be a good thing.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? Using ad blockers – I totally get why – but want to support the site? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()

[ad_2]

Source link