The disconnect between demand destruction from interest rate hikes and demand creation from infrastructure spending – Ahead of the Herd

2022.06.29

Last week was a bad one for mining & metals.

Amid fears of an industrial slowdown across major economies, the metals sector is on track for its biggest quarterly drop since 2008 — a dramatic reversal following two years of gains, driven by a combination of strong post-covid demand, supply chain disruptions and inflation.

Prices are falling due to worries about tepid economic growth particularly in China, the world’s top buyer of commodities. First-quarter GDP growth of 4.6% was nearly half of China’s 8.1% average last year, and way off the blistering 18.6% it managed in Q1, 2021.

Bloomberg reported that metals rebounded Monday following their worst week in a year, as China’s economy showed signs of recovery and Goldman Sachs said global supplies were still constrained (more on that below). Tin prices surged 11% in London and other base metals, including nickel and aluminum, were up, over last week.

Stock market palpitations continued on Tuesday, with the Dow dropping almost 500 points.

According to the news outlet, Chinese manufacturing activity is shrinking, European industrial output contracted for the first time in two years, and US manufacturing hit a 23-month low. Copper sunk to a 16-month nadir of $8,122 a ton Friday on the LME, and several metals from aluminum to zinc have booked losses, with the Bloomberg Industrial Metals Spot Subindex down 26% this quarter.

The rout in industrial metals started earlier this month when the US Federal Reserve increased interest rates by 75 basis points, to tackle 40-year-high inflation of 8.6% more aggressively. The sell-off accelerated last week.

I won’t sugar-coat the bad news, however, there is something else going on, behind the gloomy headlines.

According to Goldman Sachs, “metal prices are dislocated from fundamentals.” The influential bank points out that, despite a weakening on the demand side, the supply shortages we have been writing about for years, are still very much intact.

“The sharp move lower in base metals prices over the past few weeks reflects almost entirely financial liquidation pressures, rather than any deterioration in fundamental conditions,” Goldman analysts including Jeffrey Currie wrote in a note. (the same Jeff Currie who predicts we are in the early stages of the next commodities supercycle, driven by electrification and decarbonization.

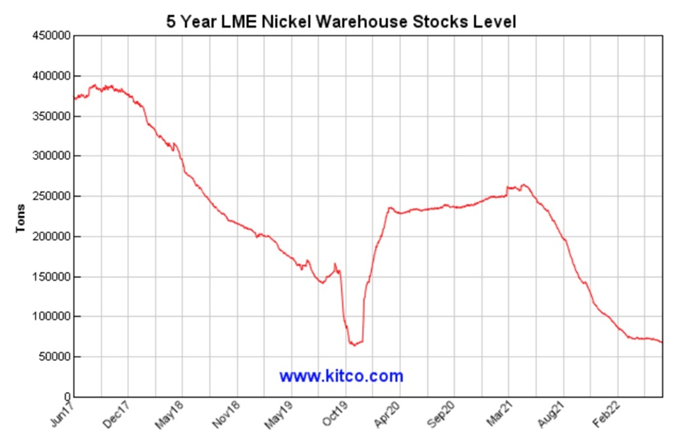

Indeed copper and other metals, like zinc, nickel and aluminum, are facing some of their tightest conditions ever, with global inventories dwindling, as the Kitco charts below show. (if demand destruction is really taking hold, why aren’t inventories growing instead of shrinking?)

A new supply crisis is reportedly brewing in the zinc market, after readily available LME inventories sunk to a record low last week.

As for the Fed, the central bank has warned it has little influence over supply-side drivers that have underpinned the recent surge in commodities.

Killing consumer demand

Instead, the Fed rate hikes will have a much greater impact on consumers’ spending, and while that could potentially be a drag on raw materials demand in areas like housing (mortgage-rate increases), automaking, and durable goods manufacturers facing higher borrowing costs, the question we are asking in this article is, will the consumer demand destruction from rising rates be enough to offset the significant demand for metals likely to accrue from the trillions worth of infrastructure investments being rolled out by several countries? At AOTH, we say it won’t even come close.

Right now there is all kinds of talk of a market meltdown and what looks like the early stages of a global recession. Some of the world’s greatest financial minds are warning that the longest bull market in history is finally over, and to batten down the hatches for the recessionary storm.

We are currently seeing consumers cracking under the pressure of 40-year high inflation. The Wall Street Journal reported US retail sales declined in May, as consumers felt the pinch from inflation, higher gasoline prices and rising interest rates that make car purchases more expensive. Economists pay close attention to consumer spending as it makes up about 70% of the US economy.

They appear to fall into two camps, one that sees the economy on the verge of deflation, brought on by a recession caused by central bank tightening; and the other that thinks high inflation will become a lingering problem even if the market crashes and we fall into recession. According to the World Bank, whether or not a recession occurs, “the pain of stagflation [low growth + inflation] could persist for several years.” (global growth is projected to slow from 6.1% in 2021 to 3.6% in 2022 and 2023, largely due to the war in Ukraine, says the IMF)

Recession, stagflation, and a weaker US dollar are all likely outcomes.

In my opinion, this will cause the Fed to reverse course and start lowering interest rates again, a repeat of the “quantitative easing” policy the Fed has been following on and off since the financial crisis.

Goldman Sachs economists expect that two 75 basis-point rate hikes over the summer could sap US growth, adding to recession fears and stoking gold investment demand.

Economies are flagging and some may even go into recession. Governments are using interest rate hikes to curb inflation, which is chipping away at consumers’ purchasing power and making the cost of everything — groceries, gasoline, housing etc. — more expensive. We understand the “demand destruction” strategy — reduce spending by making the cost of borrowing higher — but it’s only addressing the consumer demand side of the equation. The formula for aggregate demand is AD = C + I + G + (X-M) where X is exports and M is imports, and AD is another term for GDP.

For the Fed’s strategy of lessening consumer demand to work, i.e., for prices to fall, any decrease in demand from C, cannot be offset by an increase in demand from G, government spending. Otherwise, one just cancels out the other.

Yet this is precisely what governments across the globe are planning.

Infrastructure spending

Many countries need to reduce their so-called “infrastructure deficits”. Basic infrastructure such as roads, bridges, water & sewer systems, has been poorly maintained, and requires hefty investments, measured in trillions of dollars, to repair or replace.

China, the world’s biggest commodities consumer, has committed to spending at least US$2.3 trillion this year alone, on thousands of major projects, according to Bloomberg. They are part of Beijing’s most recent Five-Year Plan that calls for developing “core technologies” including high-speed rail, power infrastructure and new energy. Translation: more money will be aside in years two to five.

China’s $900 billion “Belt and Road Initiative” is designed to open channels between China and its neighbors, mostly through infrastructure investments. Dozens of countries have signed up to it, including Russia.

The “Belt” part of Belt and Road, introduced by President Xi Jinping in 2013, refers to a network of overland road and rail routes and oil/ natural gas pipelines planned to run along the major Eurasian land bridges: China-Mongolia-Russia, China-Central and West Asia, China-Indochina peninsula, China-Pakistan, Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar. They’ll stretch from Xi’an in Central China through Central Asia, reaching as far as Moscow, Rotterdam and Venice.

The “Road” is a network of ports and other coastal infrastructure projects from South and Southeast Asia to East Africa and the northern Mediterranean Sea. Read more on BRI

The G7 just unveiled $600 billion to counter China’s Belt and Road.

Over the weekend US President Biden and other G7 leaders from Canada, Germany, Italy, Japan and the European Union, announced at a summit in Germany the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII). A White House press release said the agreement “will deliver game-changing projects to close the infrastructure gap in developing countries, strengthen the global economy and supply chains, and advance U.S. national security.”

The United States has committed $200 billion in grants, federal funds and private investment over five years, with Europe pledging $316 billion and Japan promising $65 billion.

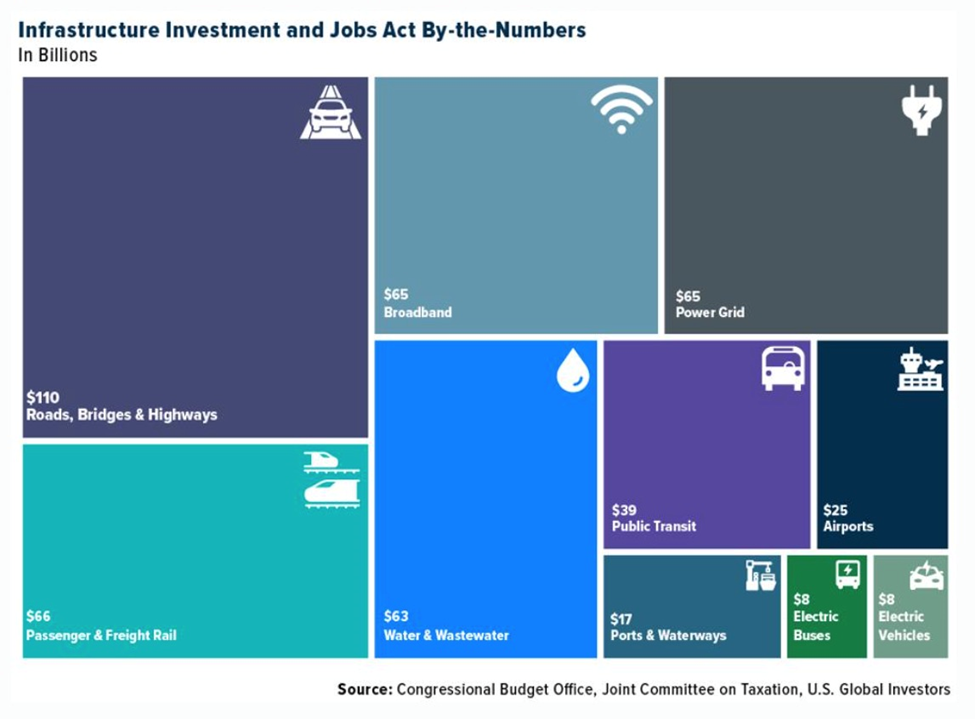

The United States is pursuing its own $1.2 trillion infrastructure package, to be spent on roads, bridges, power & water systems, transit, rail, electric vehicles, and upgrades to broadband, airports, ports and waterways, among many other items.

For such plans to work, extensive minerals are needed to build the required infrastructure, and will have to compete with one another (plus every other country) to do so, driving commodity prices higher.

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act is the largest expenditure on US infrastructure since the Federal Highways Act of 1956. Rolled out over 10 years, it includes $550B in new spending. According to S&P Global, Among the metals-intensive funding in the legislation is $110 billion for roads, bridges, and major projects, $66 billion for passenger and freight rail, $39 billion for public transit, and $7.5 billion for electric vehicles.

In particular the spending package, signed into law on Nov. 15, 2021, is expected to be a boon to domestic steel and aluminum production. The American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI) estimates that every $100 billion invested in infrastructure, could increase demand for US steel by up to 5 million tons.

The infrastructure bill should also significantly boost domestic aluminum consumption that is already accelerating due to the “light-weighting” and electrification industrial trends, states S&P Global. For example, aluminum is widely used in the electrical grid, which will receive $65B as part of the legislation.

See below for an interesting graphic, published by Frank Holmes of US Global Investors, on how the total $1.2 trillion will be allocated.

Holmes cites Morgan Stanley analysts, who say the biggest recipient materials of the infrastructure package would be cement, sand & gravel, and finished steel products such as rebar.

Electrification & decarbonization

An extension of the infrastructure buildout is the global transition towards a “green economy”, which can only be accomplished with renewable power, electric vehicles and energy storage technologies.

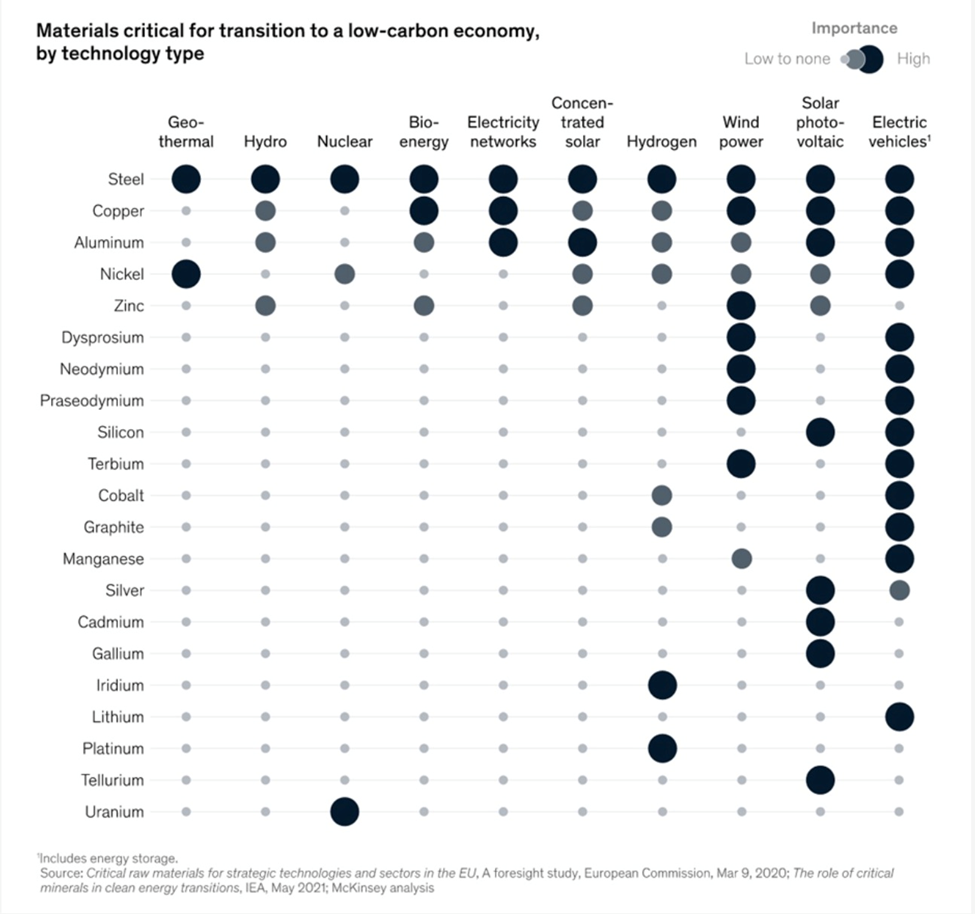

All of these require lots of minerals. The amount of raw materials we’ll need to extract from the Earth to feed this transition is staggering.

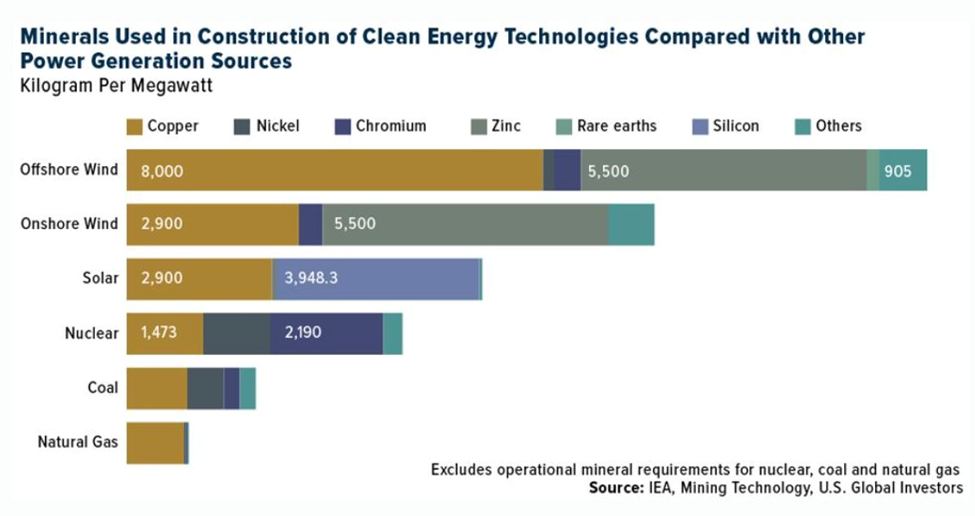

EVs require, on average, six times the amount of minerals such as nickel, copper, cobalt and lithium, as traditional gas-powered cars. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), an offshore wind farm uses nine times as many resources as a natural gas plant, with 8,000 kg of copper needed to produce just one megawatt of power (1GW = 1,000MW)

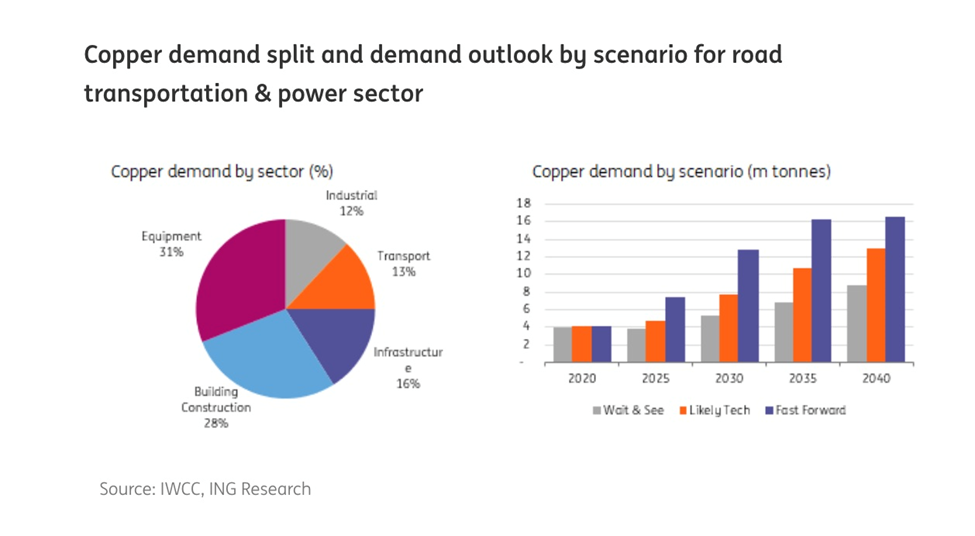

ING analyzed how the transportation and power sectors are likely to affect the demand for metals expected to benefit from the energy transition, including copper, aluminum, nickel, cobalt and aluminum.

The 2021 study by the Dutch banking group separated the demand for each of the above metals into three scenarios: ‘Wait & See’, ‘Likely Tech’ and ‘Fast Forward’, the latter being the most aggressive scenario for metals usage.

Under ‘Wait & See’, copper demand from road transportation and the power sector grows by 117% between 2020 and 2040, equivalent to a compound annual growth rate of 3.9%. ‘Fast Forward’ demand from these two sectors grows at a CAGR of 7.2% to almost 17Mt by 2040. Current global copper consumption is estimated at nearly 29Mt.

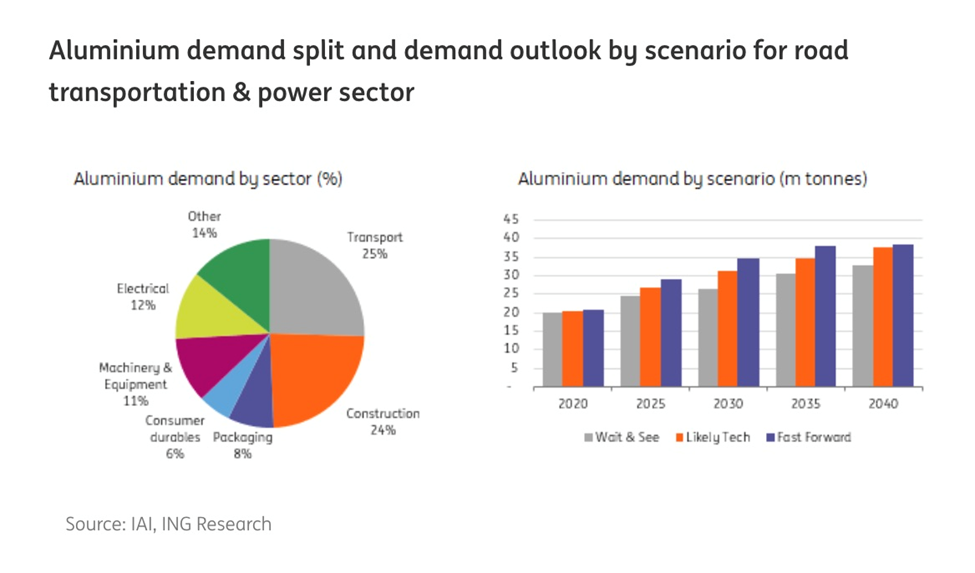

Aluminum demand for power & transportation is also expected to climb, though not as much as copper, because increased need for aluminum in EVs will be offset by declining sales of ICE vehicles which also contain the lightweight metal. Higher aluminum demand for these two sectors is expected to be driven by increased wind and solar power deployment, as well as above-ground transmission and distribution lines. Under ING’s ‘Wait & See’ scenario, aluminum demand grows at an average 2.5% per year, while Fast Forward’ sees demand increasing by a little over 3% per annum between now and 2040, or slightly more than 20Mt to 38Mt by 2040.

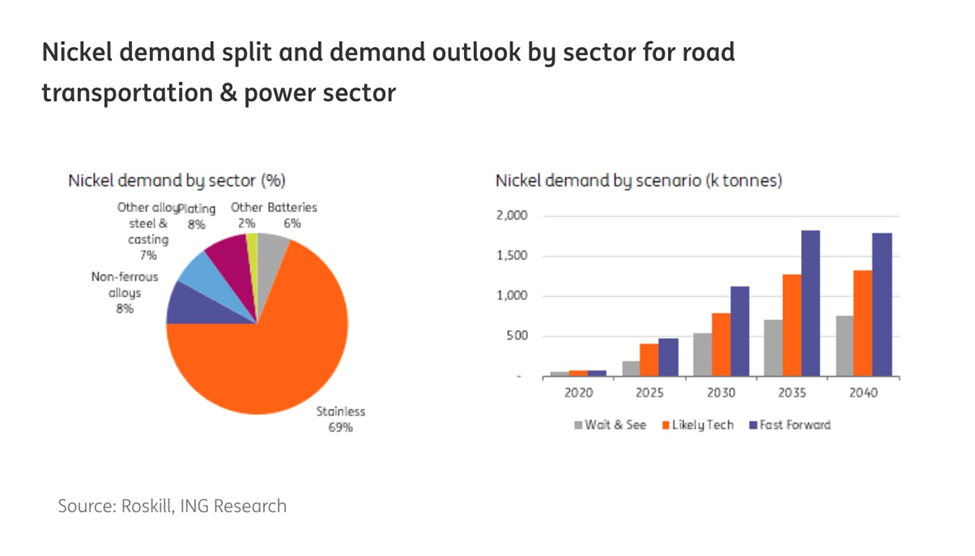

Current nickel demand of ~2.4Mt per annum is dominated by stainless steel, which accounts for about 70% of the market. The battery industry by comparison is just 6%, but that figure is expected to grow exponentially due to electric vehicles. According to ING, nickel demand for road transportation and power under ‘Wait and See’ grows to 13.2% between now and 2040, 15.3% under ‘Likely Tech’ and 16.8% under the ‘Fast Forward’ scenario.

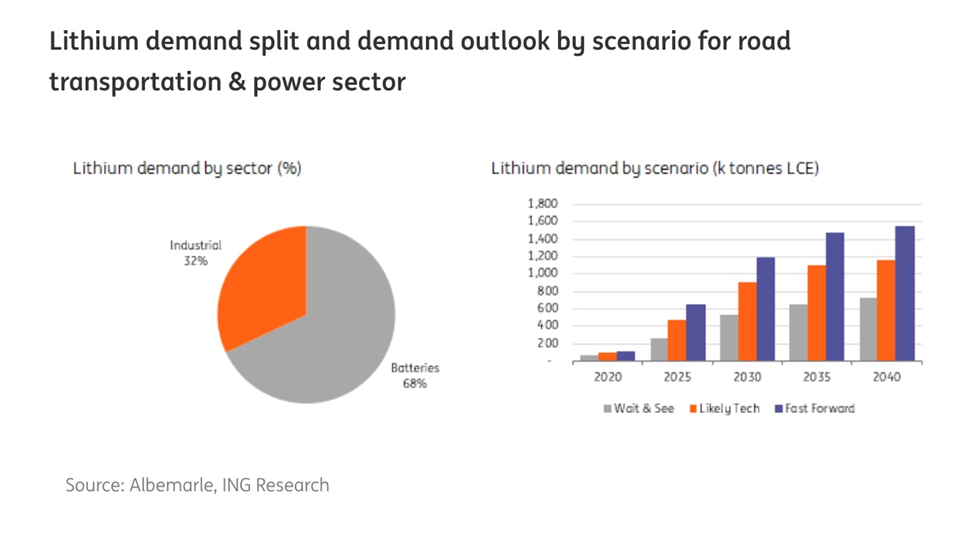

Other EV battery metals lithium and cobalt will also see double-digit increases in usage. Most of the growth for lithium, naturally, will be in road transportation, compared to stationary energy storage capacity, which represents a fraction of the lithium market compared to EVs.

Under ING’s ‘Wait and See’, total lithium demand from EVs and power grows by 13% per annum from now until 2040. In the ‘Fast Forward’ scenario, annual demand growth is around 14%, pushing annual demand from these two sectors alone at 1.6Mt, by 2040 — more than five times current global lithium demand (all uses) of 290,000 tonnes lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE).

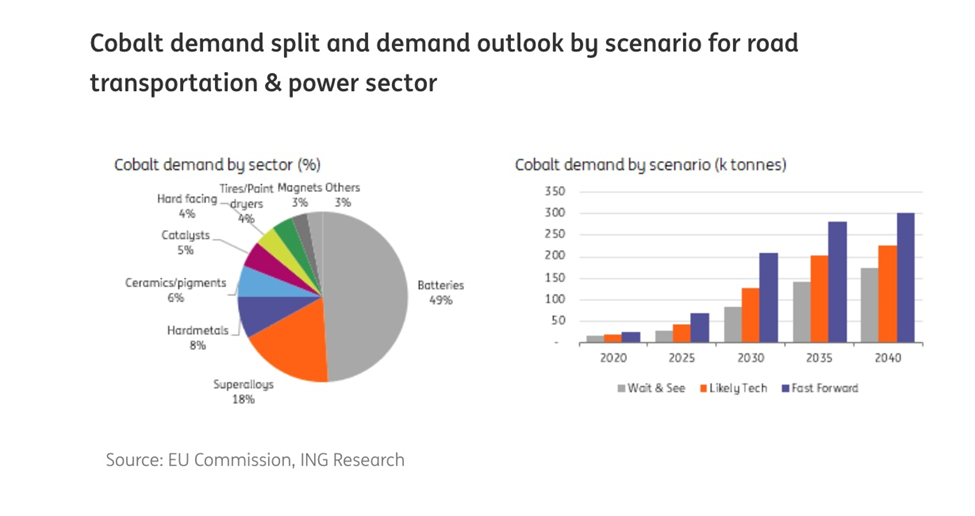

Like nickel and lithium, cobalt demand will be largely driven by the transportation sector, as long as its usage in electric-vehicle battery chemistries remains relevant (some EV-makers are trying to reduce the amount of cobalt in their batteries due to supply risk, with two-thirds of current cobalt supply coming from the unstable DRC).

Under the ‘Wait and See’ scenario, cobalt demand grows by 12.8% a year until 2040, 13.2% under ‘Likely Tech’, and 13.6% under ‘Fast Forward’.

All in all, BNEF estimates that the global transition will require about $173 trillion in investments over the next three decades; every commodity under the sun will be gobbled up.

Macro drivers

On top of the trillions worth of government infrastructure spending expected to be rolled out over the next few years, and hundreds of billions more in fiscal outlays related to the electrification of the global transportation system, and the decarbonization of fossil-fueled energy sources, the usual commodities demand drivers, i.e., population growth and urbanization, are still very much in play.

Urbanization

Population rise goes together with urbanization, since our modern world, and economic system, revolves around urban centers, where most of the jobs, infrastructure and services are.

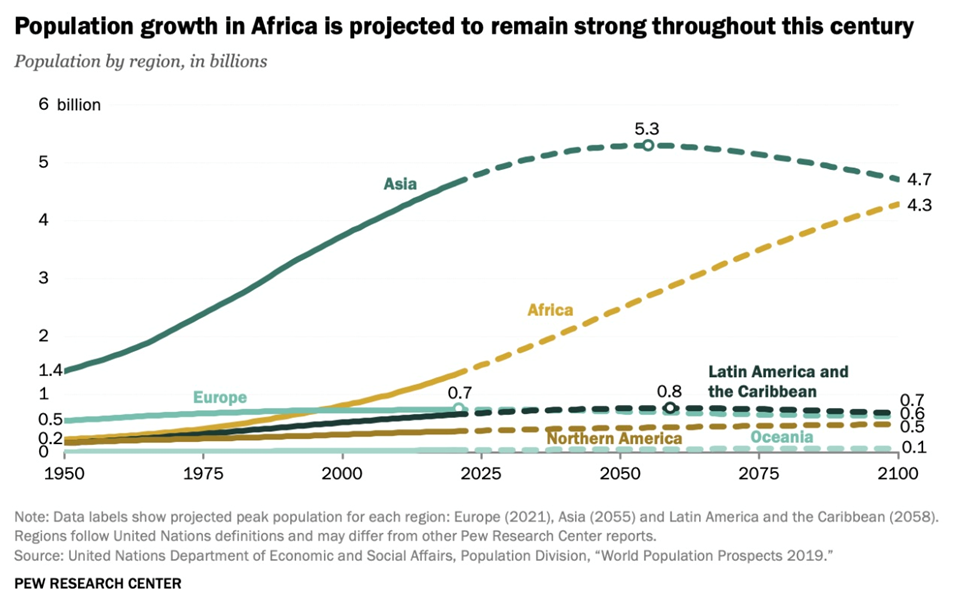

According to the United Nations, by 2050 over two-thirds of the population, 68%, will live in cities, compared to 55% as of 2018. Projections shows that the gradual shift from rural to urban areas will add close to 2.5 billion people to cities in the next 28 years, with the majority of this increase taking place in Asia and Africa.

Population growth

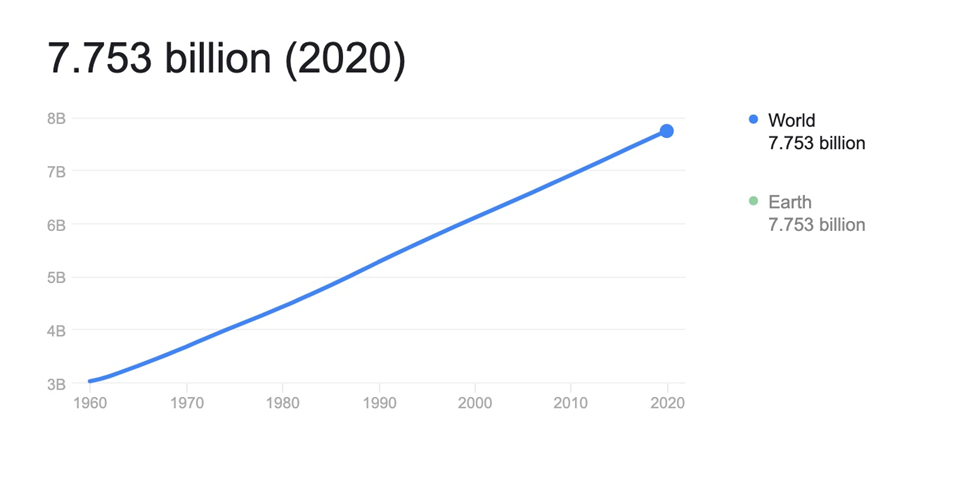

Since 1950, the world’s population has gone from 2.5 billion people to 7.753 billion. The UN projects it will reach 9.8 billion by 2050.

Among the most interesting findings of Pew Research, which studied the topic based on United Nations figures, are the following:

- By 2100, the world’s population is projected to reach approximately 10.9 billion, with annual growth of less than 0.1% – a steep decline from the current rate [1% to 2%].

- In the Northern America region, migration from the rest of the world is expected to be the primary driver of continued population growth. The immigrant population in the United States is expected to see a net increase of 85 million over the next 80 years (2020 to 2100) according to the UN projections, roughly equal to the total of the next nine highest countries combined. In Canada, migration is likely to be a key driver of growth, as Canadian deaths are expected to outnumber births.

- India is projected to surpass China as the world’s most populous country by 2027. Meanwhile, Nigeria will surpass the U.S. as the third-largest country in the world in 2047, according to the projections.

- Between 2020 and 2100, 90 countries are expected to lose population. Two-thirds of all countries and territories in Europe (32 of 48) are expected to lose population by 2100. In Latin America and the Caribbean, half of the region’s 50 countries’ populations are expected to shrink. Between 1950 and 2020, by contrast, only six countries in the world lost population, due to much higher fertility rates and a relatively younger population in past decades.

- The population of Asia is expected to increase from 4.6 billion in 2020 to 5.3 billion in 2055, then start to decline. China’s population is expected to peak in 2031, while the populations of Japan and South Korea are projected to decline after 2020. India’s population is expected to grow until 2059, when it will reach 1.7 billion. Meanwhile, Indonesia – the most populous country in Southeastern Asia – is projected to reach its peak population in 2067.

- Africa is the only world region projected to have strong population growth for the rest of this century. Between 2020 and 2100, Africa’s population is expected to increase from 1.3 billion to 4.3 billion.

- Six countries are projected to account for more than half of the world’s population growth through the end of this century, and five are in Africa. The global population is expected to grow by about 3.1 billion people between 2020 and 2100. More than half of this increase is projected to come from Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania, Ethiopia and Angola, along with one non-African country (Pakistan). Five African countries are projected to be in the world’s top 10 countries by population by 2100.

Africa rising

Regarding the last three bullet points, in a previous article, we dove deeply into Africa’s population rise and its natural resource growth.

According to the Center for International Policy, in 2035 the number of working-age people in Africa will exceed the rest of the world combined, and by 2050 one in four humans will be African. At 2100, 40% of Earth’s population will hold a passport from an African country.

The Center for International Policy points out that Africa’s impending “demographic dividend” will no doubt increase its economic clout:

Since 2000, at least half of the countries in the world with the highest annual growth rate have been in Africa. By 2030, 43 percent of all Africans are projected to join the ranks of the global middle and upper classes. By that same year, household consumption in Africa is expected to reach $2.5 trillion, more than double the $1.1 trillion of 2015, and combined consumer and business spending will total $6.7 trillion.

Sub-Saharan Africa has done exceptionally well, buoyed by higher commodity prices, an improved global economy and better access to capital markets, reports Quartz.

According to the ‘Movers’ ranking by US News, among the world’s 10 fastest growing economies, three are in Africa. United Arab Emirates was rated #1, Egypt was third and Saudi Arabia was 10th.

A finite world

What does steady population growth, at least to the year 2100, and urbanization mean for commodities? The answer is too many people chasing too few resources.

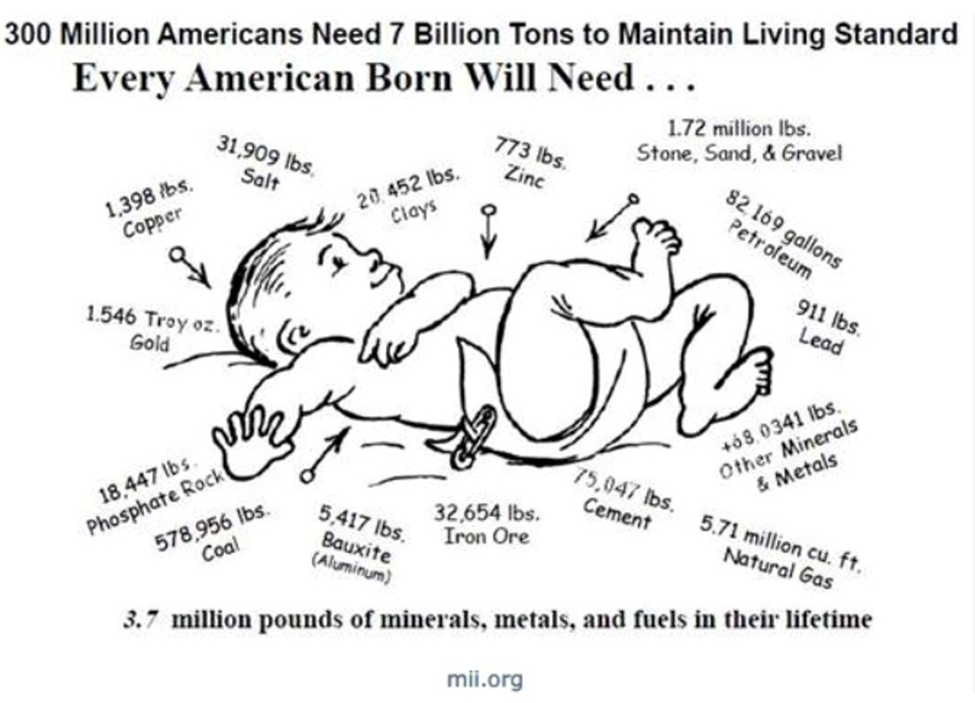

The countries with the most natural resources are, in order: China, Saudi Arabia, Canada, India, Russia, Brazil, the US, Venezuela, the DRC and Australia.

Another 2.1 billion people will be added to the world between now and 2050. Most will not be Americans but they are going to want a lot of things that we in the Western developed world take for granted: electricity, plumbing, appliances, AC etc. What if all these people were to start consuming, over the next 28 years, just like an American? As developing nations get richer, people with more money in their pockets are all going to want to eat more and better foods; it’s said they will “climb the protein ladder”. When grain and oilseed production is converted into meat protein and fuel, this effect is magnified.

What’s going to happen to the world’s minerals if 2 billion more “Americans” are added to the consuming class? Here’s what each of them would need to consume, per year, to live the American lifestyle:

The question is, will everyone be able to buy enough resources to live like an American? The answer is a resounding no!

Another way to look at this, is based on population growth statistics, by 2050 the world economy will be four times larger than today. To have the same per-capita consumption of Canada would require a world economy 15 times its current size!

Worldwatch reports the planet currently has 1.9 hectares of productive land per person to supply resources and absorb wastes, but the average person uses 2.3 ha. An American has an ecological footprint of 9.7 ha versus the average resident of Mozambique who uses just 0.47 ha.

Can we produce enough food, metals and energy to handle 15 times more economic activity by 2050? No. We neither have the resources in the ground, nor the amount of land, water and fuel required.

If you don’t believe me, take copper and an example. Total mined copper was 20 million tonnes in 2021.

Global refined copper demand has risen steadily from 2005, when it was around 18 million tonnes, to the current global consumption of about 28 million tonnes. Immediately we can see that demand is currently outstripping supply by about 7 million tonnes, annually.

Even if we mined every last discovered, and undiscovered, pound of land-based copper, the expected 8.2 billion people in the developing world would only get three quarters of the way towards copper use parity per capita with the US, if we assume 9.8 billion by 2050.

Of course the rest of us, the other 1.6 billion people expected to be on this planet by 2050, aren’t going to be easing up, we’re still going to be using copper at prestigious rates while our developing-world cousins play catch up. Copper-use parity isn’t going to happen, it can’t.

Running short

The adage “if it can’t be grown it must be mined” serves as a reminder that electric vehicles, transitional energy, and a green economy start with metals. The supply chain for batteries, wind turbines, solar panels, electric motors, transmission lines, 5G — everything that is needed for a green economy — starts with metals and mining.

In fact, battery/ energy metals demand is moving at such a break-neck speed, that supply will be extremely challenged to keep up. Without a major push by producers and junior miners to find and develop new mineral deposits, glaring supply deficits are going to beset the industry for some time.

Swiss investment bank UBS predicts large deficits by 2030 for each of these metals, and remember this is just for the switch from a fossil-fueled based transportation system to an electrified one: 170,000 tonnes for cobalt, equal to 42% of the cobalt market; 10.9 million tonnes of copper (about half of current global mined production), representing 31% of the market; 2.1Mt for lithium (50% market share); 3.7Mt for natural graphite and 2.2Mt for nickel (both 37%); and 48,000 tonnes for rare earths, equivalent to 47% of the market.

We already know we don’t have enough copper for more than a 30% market penetration by electric vehicles. For solar power we are talking about finding 16 times the current annual production of aluminum, and 23 times the current global output of copper. Up to six times the current production levels of nickel, dysprosium and tellurium are expected to be required for building clean-tech machinery.

Even if the mining industry could identify and produce this amount of metals to meet the world’s goal of 100% decarbonization, the supply shortages guaranteed to hit the markets for each would make them prohibitively expensive. It’s just supply and demand.

Most natural resource modeling has greatly overstated the amount of fossil fuels and minerals the petroleum and mining industries will be able to extract. Forecasters assume that as long as we have the technological capability, and resources are still in the ground, extraction will follow.

In fact this model greatly overstates the quantity of future resources that can actually be mined. The reason is because the world economy tends to run short of many types of resources simultaneously.

Take January 2022 as an example. World Bank Commodities Price Data shows prices were high for a number of materials including fossil fuels, fertilizers, aluminum, copper, iron ore, nickel, tin and zinc.

But that doesn’t mean producers will automatically go after these commodities. For several minerals, including copper, grades are declining, meaning more ore has to be mined for the deposit to be economic. More complicated mineralogy often means more complicated, and more expensive, metallurgy.

Over the past 10 years, greenfield additions to copper reserves have slowed dramatically, with tonnage from new discoveries falling by 80% since 2010.

Arguably, we are at the point where no significant new technologies will be invented to make mining more efficient or profitable — unlike the “shale revolution” brought about by directional drilling and hydraulic fracturing i.e. fracking. These processes allowed previously uneconomic “tight” oil and gas formations to be drilled, transforming the United States from a net oil importer to a net oil exporter.

In the same way, farming and ranching have reached the limits of technology. The agricultural reforms and resulting production increases fostered by the Green Revolution are responsible for avoiding widespread famine in developing countries and for feeding billions more people since. Unfortunately though, high-yield growth is tapering off and in some cases declining. This is mostly because of an increase in the price of fertilizers, other chemicals and fossil fuels, but also because the overuse of chemicals has exhausted soils and irrigation has depleted aquifers.

Throw climate change into the mix, and you’re looking at a serious problem.

A warming planet also affects minerals extraction and processing. For example Chile, the world’s biggest copper producer, has problems with water and is having to desalinate seawater used for mining copper in the country’s arid north. We are already seeing major copper mines in Chile having to curtail production due to water shortages brought on by a +decade-long drought.

Last summer in central Brazil, the worst water crisis in nearly 100 years made navigation on one of the country’s most important river systems difficult, making it more challenging and costly to get its grains and iron ore to global markets. (flows were @ 55% of the historical average).

Beyond climate change and technical constraints on minerals extraction, there is also the considerable time lag involved in developing new supplies. In Canada and the United States, it can take up to 20 years for a new mine to come online, from the initial discovery phase to commercial production.

Finally, resource nationalism is throwing up a number of impediments to bringing promising deposits into production.

Countries rich in minerals are frequently looking at ways to get more money from miners, the most common tactic being to hike royalty payments.

Governments have also gone beyond taxation in getting more out of the mining sector with requirements such as mandated

beneficiation/export levies and limits on foreign ownership:

- Mandated beneficiation/export levies – Governments are imposing steep new export levies on unrefined ores. Minerals processed in-country capture more of the value chain as the products achieve higher prices.

- Increasing state ownership – Miners are easy targets because mining is a long-term investment and one that is especially capital intensive. Mines are also immobile, so miners are at the mercy of the countries in which they operate. Outright seizure of assets happens using the twin excuses of historical injustice and environmental or contractual misdeeds. There is no compensation offered and no recourse.

Risk consultancy Verisk Maplecroft tracks incidents of direct expropriation and nationalization, summarizing the degree of risk in an annual resource nationalism index.

Sixty six of 198 countries in the latest (2021) index, or 33%, have tightened their grip on resource wealth since 2017. Latin America, especially Chile and Peru, stands out as the region where the risk of expropriation and tax increases have increased the most.

Conclusion

The markets for industrial metals are correcting, after two years of steady gains.

Investors are scared stiff of inflation, not only the damage that higher prices inflict on consumer spending and confidence, but the negative impact of higher interest rates on corporate earnings, mortgage payments, industrial output and economic growth.

We understand the rationale behind interest rate increases — hike rates to make the cost of borrowing more expensive, thereby dampening demand and bringing prices down. The problem is, this inflation is not demand-driven, it’s supply-driven.

With respect to metals, the fact is that monkeying with the consumer demand side of the aggregate demand equation (AD = C + I + G + (X-M)) will only have a limited dampening effect on prices, because there is all this government infrastructure/green transition spending planned (G in the equation), that will have the opposite effect on prices.

In normal circumstances, high metal prices could probably be brought down on the demand side through interest rate hikes. For example, if people buy less cars, because car loan interest is higher, automakers will make less cars. They will demand less aluminum, steel, copper and other materials, thereby bringing down their sticker prices.

In today’s environment, though, the challenges on the supply side are daunting. Between China, the United States, Europe and Japan, we are talking about $2.3 trillion + $1.2 trillion + $600B + $900B = $5 trillion in infrastructure commitments. Among the materials likely to be highly demanded for these projects, are steel, rebar, aluminum, cement, sand and gravel. There will also be large amounts of copper required for wiring and plumbing, nickel-containing stainless steel reinforcement on bridges, zinc coatings used as corrosion protection for steel bridges etcetera etcetera etcetera, the list of metals goes on.

For China’s Belt and Road Initiative alone, the International Copper Associates estimates the demand for copper in over 60 Eurasian countries, could hit 6.5 million tonnes by 2027, a 22% increase from 2017 levels.

Then there’s the electrification and decarbonization imperative.

Population explosion and urbanization, particularly in Asia and Africa, are macro demand factors pressuring supply. Climate change and resource nationalism are also throwing up impediments to bringing promising mineral deposits into production or expanding existing ones.

At AOTH, we believe the commodities bull market is only just beginning.

At present levels, commodity prices would have to surge 600% to become overvalued relative to the stock market. If the stock market falls 50%, commodity prices would still have to rise 250% to enter “radically overvalued” territory.

Commodities are currently valued below financial assets. That will change because we live in a finite resource extraction challenged world while our demand is growing and infinite.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

[ad_2]

Source link