The Fed’s Repo And Reserve Payouts Have Populists In A Bind

WASHINGTON, DC – SEPTEMBER 28: Chairman Sherrod Brown (D-OH) questions Treasury Secretary Janet … [+]

Last week, Senate Banking Committee Chairman Sherrod Brown (D-OH) sent an open letter to Fed chair Jerome Powell reminding him the Fed is also required to “promote maximum employment” while fighting inflation. Senator John Hickenlooper (D-CO) then released his own letter, asking Powell to “pause and seriously consider the negative consequences of again raising interest rates.”

I doubt that Powell or anyone else at the Fed has forgotten about the maximum employment portion of their mandate, and I’m even willing to bet that Powell and his colleagues share the senators’ concerns. They’re more than aware of those “negative consequences” that have so many senators concerned, and they know that over-tightening could cause a recession. Nobody at the Fed wants that outcome.

But that’s politics.

Speaking of politics, Senator Brown’s constituents would probably like to know how he feels about the Fed’s interest payment policies. Brown is known to stick up for the little guy, and his letter expressed his concern for “lower-income families” having “less wealth” and less ability to “realize gains during an economic recovery” relative to “upper-income households.”

So, it would be great to know how Brown feels about the Fed paying billions of dollars in interest to large banks and mutual funds. That’s exactly what the Fed is doing with its interest payments on bank reserves and on reverse repurchase agreements (repos), and it doesn’t seem very populist.

For anyone who has not been keeping up with these programs, here’s a quick recap.

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, the Fed shifted to a new operating framework. As a result, its main monetary policy tool is now the payment of interest on reserves. For years, economists referred to this mechanism as interest on excess reserves (IOER), but in 2020 the Fed removed all reserve requirements, so there are no longer any excess reserves.

Regardless, the Fed is now paying banks 3.15 percent interest on those reserves. (Technically, depository institutions and a few other financial institutions are eligible to receive these payments. But after reading 12 U.S. Code 461(b)(1)(A) and 12 U.S. Code 461(b)(12)(C), it will be a relief to just refer to them as “banks” instead.)

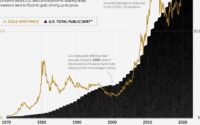

Collectively, banks are now sitting on almost $3 trillion in reserves, and the bulk of that money is held at the largest institutions, not the smallest ones. These payments are one of the reasons the Federal Reserve is now officially in the red, losing several billion dollars instead of remitting money to the U.S. Treasury.

Another major contributor to these losses is the Fed’s interest payments through its overnight reverse repurchase agreement facility (RRP). Under the RRP, which is also part of the post-2008 crisis operating framework, the Fed currently pays an overnight rate of 3.05 percent. The RRP is open to the Fed’s primary dealers and other eligible counterparties.

To qualify as a reverse repo counterparty, one basically has to be either a bank with at least $30 billion in assets, a government sponsored enterprise (the Federal Home Loan Banks, Fannie Mae, and Freddie Mac), or a large money market mutual fund.

The RRP facility currently has more than $2 trillion outstanding. So, the largest financial institutions in the world are parking their cash at the Fed for an overnight rate of return of 3.05 percent. (For more details on how the RRP works, here’s a summary.)

Obviously, that’s a great deal if you can get it. And most people can’t.

One month Treasury rates are about 3.5 percent, and few money market mutual funds are offering anyone 3 percent or more, on any terms.

As it should, the Fed makes the full list of RRP mutual fund counterparties and their specific funds available to the public. A little work reveals that, as of last week, these funds offer their investors an average 7-day yield (depending on the class of shares) of about 2.5 percent. Many of these funds are not open to individual investors, and about half require a minimum investment of more than $100,000.

For instance, BlackRock Fund Advisors lists the Money Market Master Portfolio, Feeder Fund: BCF Institutional Fund. This fund offers a 3.23 percent 7-day yield, but it is only open to companies for which Blackrock (or its affiliates) serve an advisory or administrative role. And it has a minimum investment requirement of $100 million. Goldman Sachs has similar funds, offering institutional investors 7-day yields that range from 2.46 percent to 3.09 percent, with minimum investments that range from $1 million to $10 million.

To be fair, the list is not exclusively large institutional funds with high minimums. For example, Invesco has a government and GSE fund listed, with no minimum investment requirement, that offers 2.39 percent to individual investors. But that’s certainly not the norm for this list.

Obviously, most of these large institutional funds have individual investors, but the fact remains that those people are not receiving (fully guaranteed) overnight rates of 3 percent.

Perhaps Senator Brown is fine with this arrangement. Perhaps he believes that the Fed must support these large financial institutions because they are, in fact, supporting the lives of millions of workers and retirees in those lower-income categories.

If that’s the case, that would be an interesting shift in Brown’s philosophy regarding how large corporations help people.

Regardless, if rates continue up, this arrangement is only going to get more costly and further expose the Fed for what it did in the wake of the 2008 crisis.

I’ve always argued that if Congress believed funneling money to large financial institutions was the way to go, they should have raised, borrowed, and appropriated the money as they would have done for any other federal program. Aside from the initial TARP program, that’s not what Congress did. They gave the Fed all kinds of discretion and used the institution for cover.

The result is the present-day monetary system that pays billions of dollars to large financial institutions. This system literally keeps trillions of dollars sitting at the Fed, providing incentives against finding investment opportunities in the private economy.

Perhaps Senator Brown and his colleagues believe that lower-income Americans are not paying for this arrangement.

(Nicholas Thielman provided research assistance for this article. Any errors are my own.)

[ad_2]

Source link