Federal Reserve Must Tighten 9% to Break Core Inflation’s Back

“I must share his shocking findings with you. He and I are on the same page. We both believe there is no way that the Fed can break the back of core CPI inflation in this economic cycle” – Soc Gen’s Edwards.

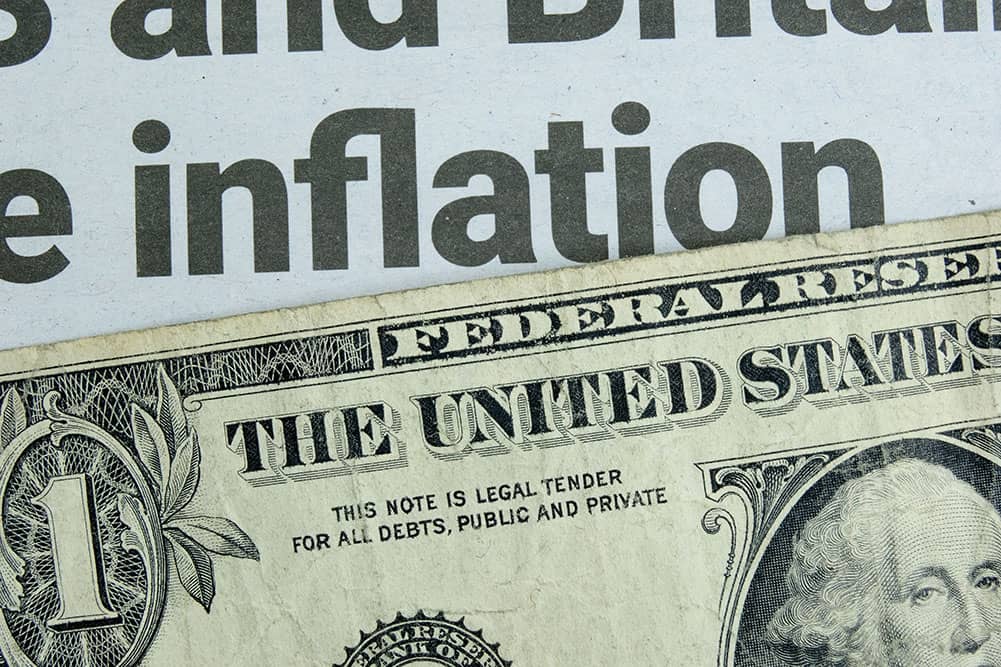

Image © Adobe Images

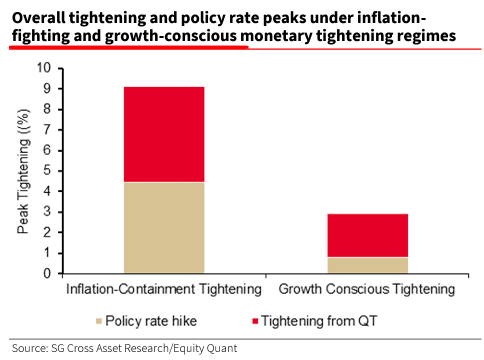

The Federal Reserve will fail to bring core inflation below 3.0% in the current cycle shows new research unless they deliver “9% overall of monetary tightening”, paving the way for a successive cycle of rate hikes that will take interest rates to levels investors are not prepared for.

This is according to Professor Solomon Tadesse, an economist at Société Générale, who finds “years of fiscal indiscipline and deficit financing have created a historic challenge for monetary policy”.

It adds to a growing body of economist research that suggests the Fed will simply be unable to achieve its aim of bringing inflation back to target for fear of breaking the economy.

This opens up the potential for a new monetary policy regime that risks wrecking central bank credibility, a second successive rate hiking cycle and a period of protracted stagflation: scenarios these leading economists don’t think markets are prepared for.

“Our New York-based Quant guru Solomon Tadesse has been a market leader in his work on folding the impact of QE (and now QT) into an overall monetary framework,” says Albert Edwards, Global Strategist at Societe Generale Corporate & Investment Banking.

“I must share his shocking findings with you. He and I are on the same page. We both believe there is no way that the Fed can break the back of core CPI inflation in this economic cycle,” he adds.

The implication is that although headline CPI inflation might fall below zero, core CPI gets stuck nearer to 3% despite the coming recession.

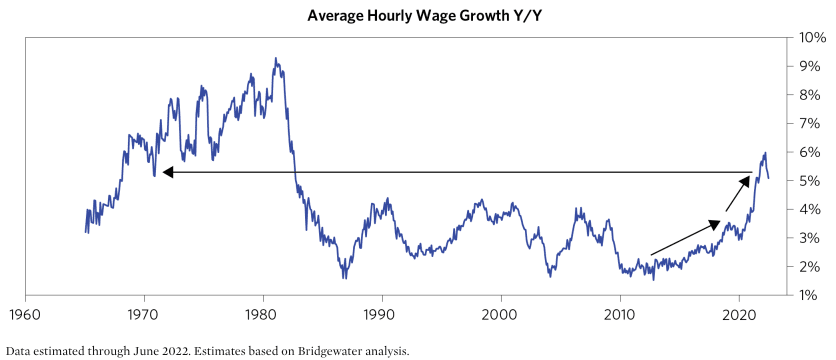

“A big near-term decline in wages is unlikely because labor markets are now tight. The unemployment rate is near its lows, job offers are plentiful, and the cost of living is giving people reason to ask for more,” says Bob Prince, Co-Chief Investment Officer for Bridgewater Associates.

“Thus, the degree and duration of the tightening must be strong enough and long-lasting enough to bring credit growth down by enough (roughly by half) for long enough—to bring spending down by enough for long enough—to weaken labor markets by enough—to bring wages down by enough—that NGDP growth falls by enough and stays there—to bring inflation down to 2.5%,” he adds.

Tadesse’s quantitative models show that more than 9% of overall monetary tightening will be required to break inflation.

(Overall monetary tightening = rate hikes + quantitative tightening. Tadesse’s calculations suggest every $100BN in quantitative tightening equates to the equivalent of just 12bp in rate hikes.)

Above: The work that must be done, and the work that will likely be done.

Currently, the market envisages the Fed to take their basic rate to a peak of 5.0% in 2023 before cutting back to 2.5% by 2025, with quantitative tightening running at around $100BN a month.

“Virtually all of the market’s attention is focused on Fed Funds, but it is the sheer magnitude of the near $4tn of QT that he estimates would be required to break inflation that Solomon thinks investors will be shocked by,” says Edwards.

Tadesse estimates that at the current run rate of c.$100BN a month, quantitative tightening would have to be accelerated dramatically.

“Can the Fed do it and will it do it? Those are the key questions – and the answer is of course it can’t. Markets are too fragile,” says Edwards.

Soc Gen reckons the Fed might have to bin their current inflation targetting framework to accommodate market stability and an inflation mandate.

As such, the inflation target could be lifted from 2% to 3% at some point in the future.

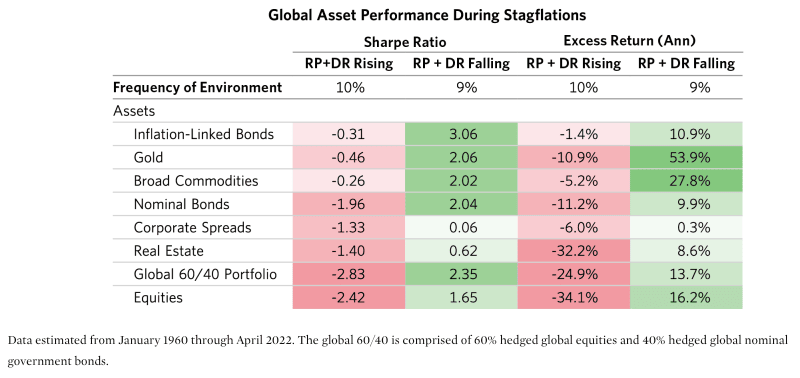

Above: Stagflation trades, image courtesy of Bridgewater.

“The alternative is the Fed ‘just’ raises the inflation target. Paul Volker himself said it was “silly” to be too obsessed with 2% as some Holy Grail. Watch this space. If the Fed does jack up the inflation target next year, we will indeed be crossing the Rubicon – again,” says Edwards.

This is a view shared by economist Oliver Blanchard at the Peterson Institute for International Economics who recently wrote:

“While a higher inflation target is desirable, the right target for advanced economies such as the US might be closer to 3 per cent than our original 4 per cent proposal.”

Prince also doubts that policymakers will be willing to tolerate the degree of economic weakness required to bring inflation back under control quickly.

“More likely, we see good odds that they pause or reverse course at some point, causing stagflation to be sustained for longer, requiring at least a second tightening cycle to achieve the desired level of inflation. A second tightening cycle is not discounted at all and presents the greatest risk of massive wealth destruction,” he warns.

Steven Blitz, Chief US Economist at TS Lombard, says a minor recession is not enough to truly reset the labour supply/demand imbalance and thereby send inflation back down to 2%.

“This FOMC does not have the license to do what they promise – a period of sustained below trend growth and higher unemployment until inflation returns to 2%. I have been writing this policy outcome beginning in 2020, that a 3% inflation target will become acceptable,” says Blitz.

TS Lombard says the U.S. policy risk for 2023 sees the Fed bails before unemployment even begins to rise, believing that the current inflation deceleration is their doing.

“So they take their bows, firmly believing that the 2012-19 economy is back in place as technology, ageing, and negligible population growth return to overwhelm the cycle. Only it won’t be, every cycle is different, with its unique challenges and opportunities,” says Blitz.

He says the anomaly of a long asset cycle – that of the post-financial crisis era – is now past.

“A more ‘normal’ credit/inflation cycle is about to take hold. The question is, how long until the Fed recognizes this shift – and how will they manage it,” says Blitz.

[ad_2]

Source link