Goodbye Central-Bank Independence, Hello Inflation: Macro View

By Simon White, Bloomberg Markets Live Commentator and Reporter

“There have been three great inventions since the beginning of time,” observed the economist Will Rogers: “Fire, the wheel and central banking.”

We should insert “independent” before the last of these, for it is autonomous central banks that have presided over the developed world’s low-inflation regime for the last 30 years. Yet as governments begin to re-assert their influence over monetary policy, this will be an increasing source of inflation and market instability. The prospect of returning to a low-inflation regime any time soon is diminishing rapidly.

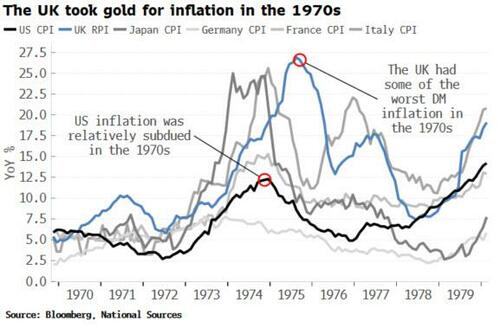

The differing experience of the UK and the US in the 1970s illustrates this. The US receives much of the attention, but it was the UK that suffered the highest and most persistent inflation of the major developed economies in that decade.

Both countries faced the same inflationary shocks, such as the Arab oil embargo in 1973, the Iranian Revolution in 1979, and the de-linking of their currencies (the dollar broke with gold in 1971, and sterling broke with the dollar in 1972). So why was inflation significantly worse in the UK?

In each country the first inflationary seeds were sown by an overestimation of the output gap. In the US, the estimate of NAIRU — the non-accelerating rate of inflation for unemployment — was significantly lower than later estimates. That meant the Fed thought it had much more room to ease than it really had, even while the government was rapidly expanding its spending in the run-up to the 1972 election.

In the UK there was a bigger overestimation. That facilitated the “Barber Boom” in 1971-74, named after then UK Chancellor Anthony Barber, of large tax cuts into a growing economy with inflation already running over 5%, as well as a major liberalization of the credit system that massively expanded bank lending and government borrowing.

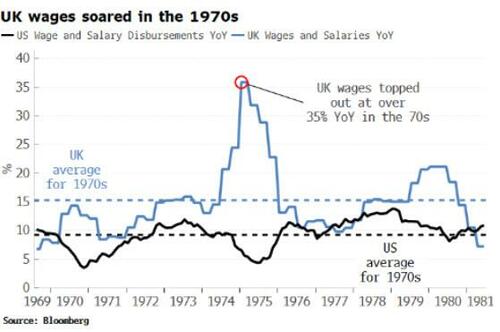

The UK’s inflationary problems were compounded by rapidly rising wages causing a significant fall in the trade balance, which drained reserves and ultimately led to the sterling crisis of 1976 and an IMF bailout.

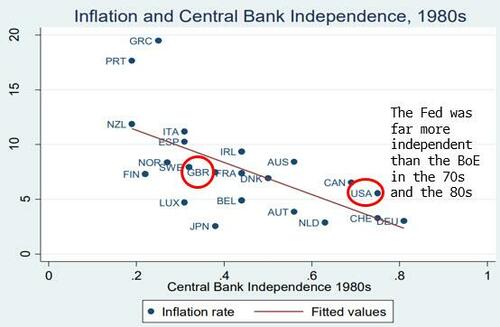

But wages and output gaps are not sufficient to explain the UK’s dismal experience in the 70s. The key factor was the much lower degree of central-bank autonomy.

The Bank of England in the 1970s had little political or operational independence. Its room for maneuver was constrained by the short maturity profile of government debt. That gave the BOE limited scope to raise rates; when it did, it led to an automatic fiscal easing as the government’s debt-servicing costs rose. In any event, the Chancellor had the ultimate authority to set interest rates in the UK, while in the US the Governor of the Fed had that responsibility (even though they could be leaned on).

The Barber Boom of a simultaneous fiscal and credit easing supported by low interest rates could not have happened so easily in the US. In the UK, on the other hand, it essentially required the say-so of only two men: the Chancellor, and the Prime Minister.

This was not only a UK and US phenomenon. The Kennedy School at Harvard in a paper from 2018 found that from the 1970s to the 1990s there was a notable relationship between central-bank independence and the level of inflation, with less independent central banks associated with higher inflation, and vice versa.

We don’t know whether it was structurally low inflation – driven by demographics and technology – that allowed governments to grant central banks more independence, or whether it was central banks that led to low inflation.

Either way, history shows that rising government influence over monetary policy has tremendous inflationary potential. The last hundred years are littered with examples – from Weimar in the 1920s to Hungary in the 1940s, to the “Stop-Go” monetary policy of the US in the 1970s – of central-bank-funded government largess leading to runaway inflation.

Decades of relative market tranquility thus threatens to be upended as the erstwhile stewards of financial stability — central banks — are elbowed aside in favor of the capriciousness of vote-hungry, inflationary-biased governments. That they did not make it on to the list of greatest-ever inventions is of little surprise.

[ad_2]

Source link