Goldman: “The World Is On The Brink Of A Rather Severe Recession”

Goldman, which like Morgan Stanley and unlike Nomura and Deutsche Bank, refuses to make a recession its base case (but is quick to make it very clear that in case of recession the S&P will drop to 3,150), has looked back at all the 77 recessions across the globe since 1961 to provide context around the current economic environment in a report titled “Revisiting Recession Facts” (available to pro subs). The report’s bottom-line according to Goldman’s Chris Hussey: some of what we are seeing today — economic overheating and large increases in rates — suggests that the world could be on the brink of a rather severe recession.” That said, the bank highlights several other aspects of the current environment which provide a buffer against a notable turndown in activity. And for once we agree with Goldman, according to which the key thing to watch is the “fiscal and monetary response to a downturn.” And since Democrats will lose Congress this November and there will be no new fiscal stimulus until 2025 at the earliest, we would add that the only thing to watch is the monetary response, i.e., when the Fed will i) cut rates back to zero, ii) resume QE and/or iii) cut rates negative.

Before we dig into the Goldman report, which looks at key facts about the frequency and severity of recessions analyzing 77 recessions in advanced economies since 1961, here are the main findings:

-

According to Goldman, the odds that the economy enters a recession in the next year at 30% in the US, 40% in the Euro area, and 45% in the UK.

-

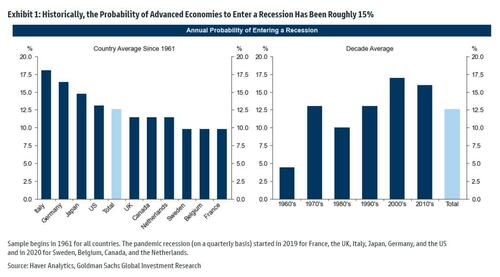

Goldman’s subjective recession probabilities are significantly higher than the average 15% annual unconditional probability of advanced economies to enter a recession since the 1960s.

-

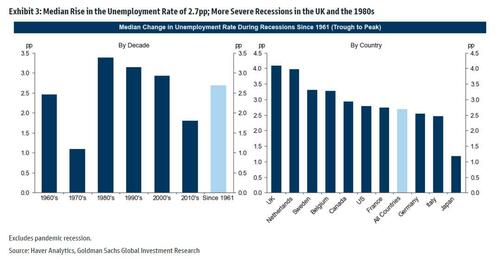

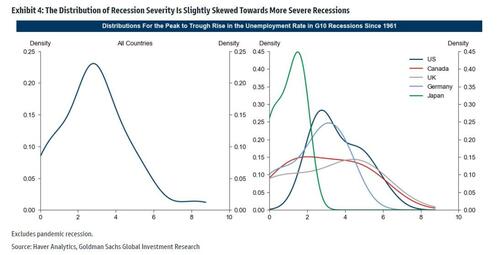

The unemployment rate has risen by 2.7% in the median advanced economy recession since the 60s with larger increases in the 1980s and the UK but smaller increases in Japan. The distribution is slightly skewed towards larger increases in more severe recessions.

-

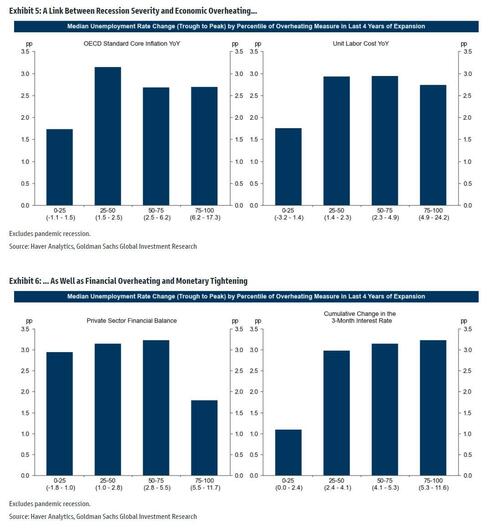

Economic overheating—high unit labor cost growth and high core inflation—and large cumulative increases in the policy rate often precede severe recessions. In contrast, elevated private sector financial surpluses often foreshadow less severe recessions.

-

Currently, across the advanced economies, unit labor cost growth, core inflation, and the expected total increase in the policy rate are generally running at levels similar to the runup of the typical advanced economy recession. Higher measures of economic overheating in the US, UK, and Canada than in Japan and the Euro area suggest that the next recession may be somewhat less shallow in these English-speaking G10 economies. In contrast, the private sector financial balance has been much higher than ahead of the typical recession for all economies, hinting at a shallow next recession.

-

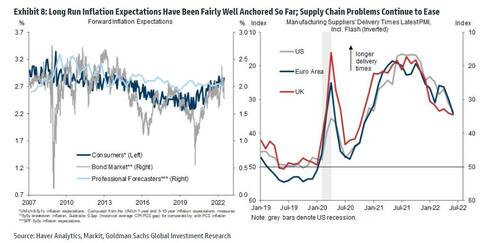

Other factors outside the historical dataset paint a mixed picture. On the pessimistic side, the monetary and fiscal policy response might be more limited than usual and energy disruptions are the main risk in Europe. On the optimistic side, long run inflation and wage expectations still appear mostly anchored and substantial supply side improvement opportunities remain.

With that in mind, let’s delve deeper into the report starting with…

Frequency

Goldman summarizes the historical frequency of recessions using official recession classifications, such as the NBER in the US, when available. Exhibit 1 shows that the annual unconditional probability of advanced economies to enter a recession since the 1960s has been roughly 15% on average. It also shows that recession risk has not varied much across countries or over time over the past several decades.

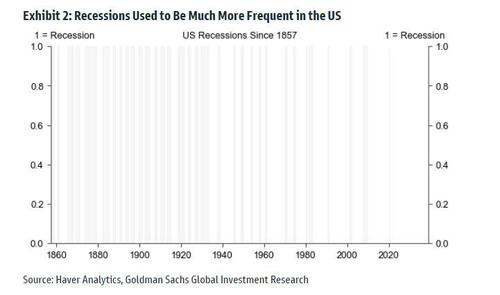

Goldman’s subjective recession probability in the US of 30% over the next year is also elevated relative to its own extended history. The annual probability of entering a recession in the US has averaged 12% since the 90’s (Exhibit 2), though it averaged a much higher 23% between 1855-1990. US recessions have become less frequent following the creation of the Federal Reserve, the anchoring of inflation expectations, and the decline in the relative importance of the cyclical manufacturing sector.

Severity

Goldman then defines the severity of recessions using the trough to peak change in the unemployment rate. The list excludes the “exogenous” pandemic recession of 2020 as increases in the unemployment rate were either outsized outliers in countries such as the US and Canada or significantly limited by furlough schemes in Europe and Japan.

Exhibit 3 shows that the unemployment rate has risen by 2.7% in the median advanced economy recession since the 60s, with somewhat larger increases in the 1980s (Exhibit 3, left). Countries with larger increases in the unemployment rate also tend to have less frequent recessions—including the UK, Netherlands, and Sweden. In contrast, countries with smaller increases in the unemployment rate tend to have more frequent recessions, such as Germany, Italy, and Japan.

The distribution of the change in the unemployment rate during recessions shows a slight skew towards more severe recessions. The distributions in the UK and Canada are especially skewed towards more severe recessions, while the distribution in Japan is skewed towards less severe recessions.

Predictors of Severity

Goldman next summarizes the predictors of recession severity focusing on variables that have a long history: it finds that economic overheating—unit labor cost growth and high core inflation (Exhibit 5)—and large cumulative increases in the policy rate often precede severe recessions. In contrast, large private sector financial surpluses often foreshadow less severe recessions.

Implications

What do these findings imply for the size of the next recession? Across advanced economies, unit labor cost growth, core inflation, and the expected total increase in the policy rate are generally running at levels similar to the runup of the typical advanced economy recession, with more overheating in the US, UK, and Canada and less in Japan and the Euro area. In contrast, the private sector financial balance has been much higher than ahead of the typical recession across advanced economies.

Taken together, Exhibits 6 and 7 paint a mixed picture about the size of the next recession in the English-speaking G10 economies.

According to Goldman, on the pessimistic side, elevated economic overheating measures point to a higher than usual right tail risk of severe recession. On the optimistic side, the bank’s strategists suggest that the large private sector surplus points to a shallow recession; what they ignore is the adverse effect of tens of trillions in lost equity value, which last time we looked is viewed as “savings” by modern economists too. So while there may be $2 trillion more in excess savings, there is $20 trillion less in stock market equity. Which is worse?

Turning to other factors outside of Goldman’s historical dataset, we again see a mixed picture.

On the pessimistic side, the monetary and fiscal policy response might be more limited than usual because policy rates remain close to their effective lower bound while both central bank balance sheets and government debt levels are very large by historical standards. Moreover, the exposure to the war in Ukraine and the risk of energy supply shortages paint a relatively negative view for Germany and Italy, especially with the possibility of gas shutdowns in the winter. On the more optimistic side, long run inflation and wage expectations still appear mostly anchored, although as even Powell will admit, that is changing fast. Moreover, substantial supply side improvement opportunities remain in both global supply chains—where delivery times have shortened—and in the labor market.

What is more relevant however, is that as Goldman writes in a separate report titled Timing the cuts, “Investors seem to be shifting focus from pricing a potential recession, to pricing future Fed cuts … for as early as 2023.” Indeed, as we have been pounding the table since early this year, the timing of those cuts is all that matters.

[ad_2]

Source link