The Great Reversal in a Higher Inflation Environment

We are not in the 1970s, at least we are confidently reassured by respected economists. Admittedly, with inflation rates soaring, there are nuanced differences between then and now.

But Britain’s rail, postal and refuse collection strikes point to an overwhelming similarity – that stagflation creates winners and losers. When real national income is depressed by oil price shocks, as in the 1970s, or the current food and energy price shocks, competing claimants in the economy compete fiercely to reclaim lost income. A wage-price spiral develops.

Milton Friedman observed that inflation is “always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”. Money is clearly an important component in the inflation process. However, strikes in the UK and tightening labor markets in developed countries suggest that no explanation of inflation can be complete without reference to the power struggle between labor and capital.

While central bankers congratulated themselves on achieving low and stable inflation during the so-called Great Moderation in the three decades leading up to the 2007-2009 financial crisis, in reality the disinflation was the result of the global labor market shock emanating from China, India and China resulted the East Europeans in the world economy.

This created a long-term downward trend in labor’s share of national income. Productivity gains were completely confiscated from capital. The disinflationary impulse was reinforced by demographic developments and the wider effects of globalization.

Weak labor returns held back consumption and output as workers have a higher propensity to consume than capital owners with higher savings rates. This led to an endemic expansionary monetary policy.

As economists at the Bank for International Settlements have long pointed out, central banks have not leaned against the bull market, but have aggressively and persistently eased in times of crisis. This policy accommodative bias was further reinforced by central bank asset purchase programs after the financial crisis.

William White, former head of the BIS monetary and economics department, argues that central banks have systematically ignored supply-side shocks and failed to grasp how much supply potential has been reduced by disease and lockdowns in the Covid-19 pandemic.

In fact, they have repeated the error of Federal Reserve Chairman Arthur Burns, who in the 1970s argued that the oil price shock was temporary while ignoring the effects of the second round, particularly on the labor market.

Speaking at the annual central bankers’ jamboree in Jackson Hole last month, Fed Chair Jay Powell pointed out that the Fed is tackling the case with delay and needs to hang in there until the job is done.” The difficulty here is that both private and public sector debt levels are higher than before the financial crisis, so the production and employment costs of sharply rising interest rates will be very high.

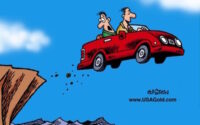

This debt trap raises acutely the long-standing question about central bank policy: How can politicians and the public be convinced that a mild recession now is a price worth paying for a much worse recession later? Central bank independence is at risk.

The Fed’s hardening stance suggests the bond bear market has much more to go. And stocks’ rally over the summer appears to have been unworldly. TS Lombard’s Steven Blitz points out that Fed policy needs to work on equities rather than credit creation as the 2010-19 and post-coronavirus expansion equates to an asset cycle, not a credit cycle. High-priced financial assets, he adds, have been the source of economic distortions in this cycle.

Correcting these distortions will reveal some notable contrasts to the 1970s. Today, the decline in the labor force and deglobalization are tilting the balance of power from capital back to work. We have moved from Great Moderation to Great Financial Crisis to Great Reversal to a higher inflation environment.

It is also a world where the toxic combination of the debt trap and shrinking central bank balance sheets will greatly increase the risk of financial crises. While commercial bank balance sheets are in better shape than they were in 2008, under-regulated, opaque non-banks pose a potential systemic threat, as illustrated by the collapse of family office Archegos last year. An important lesson of history is that after an “everything bubble,” the leverage, or borrowing, turns out to be far greater than anyone imagined at the time.

[email protected]

Source : www.ft.com

[ad_2]

Source link