Status of the Social Security Trust Fund, Income and Outgo: Fiscal 2022

Income jumped by $105 billion to a record $1.04 trillion as more people worked and earned higher wages, and contributed more.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

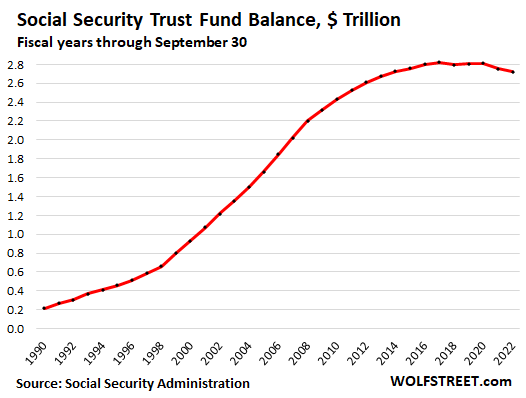

The balance in the Social Security Trust Fund – technically known as “Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund” – declined by 1.2% during the US government fiscal year through September 30, to $2.72 trillion, according to figures released by the Social Security Administration. In the prior year, the balance had dropped 2.0%; in 2018, the balance had dropped by 0.8%. Those were the only three fiscal-year declines in the fund balance since 1987.

Despite those declines, since 2010, the balance of the fund has risen by 12.1%. These figures to not include the Disability Insurance Trust Fund, which by law is a separate entity from the OASI Trust Fund, and is not part of this discussion here.

How the fund invests this $2.72 trillion.

The OASI Trust Fund invests in Treasury securities and short-term cash management securities. These securities are not traded in the secondary market, similar to the I Bonds that many readers here have at TreasuryDirect.gov.

The fact that securities in the Trust Fund are not subject to the whims of the secondary market is a good thing: The value of these holdings – similar to the value of our accounts at TreasuryDirect – doesn’t fluctuate from day to day with the whims of the secondary market. Because the Trust Fund holds Treasury securities until they mature (when it gets paid face value), the day-to-day price fluctuations are irrelevant, similar to our holdings at TreasuryDirect.

At the end of the fiscal year, the Trust Fund held $2.66 trillion in interest-bearing long-term special issue Treasury securities and $57 billion in short-term cash-management securities, called “certificates of indebtedness.”

Because these securities are not traded in the secondary market, their value equals the face value at all times, which is the amount that the Fund paid for them when it invested in them, and the amount it will be paid at maturity by the US Treasury Department.

The strategy of investing in Treasury securities and holding them until they mature is a low-risk conservative strategy that essentially eliminates credit risk.

This allows the Fund to operate with ultra-low administrative expenses, amounting to just 0.14% of the assets in the fund.

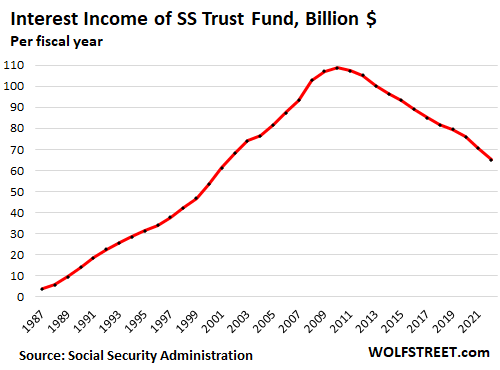

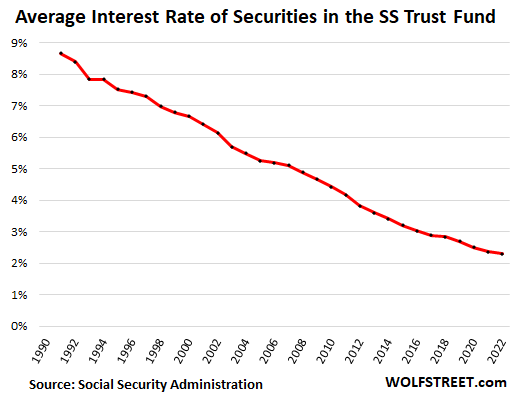

Interest income crushed by Fed’s interest rate repression.

In the fiscal year, the Fund earned $65.1 billion in interest on its Treasury security holdings. This interest income was 40% lower than in 2010, the year of peak interest, though the Fund balance was much lower at the time. The long-term securities it held were paying much higher interest rates than the new long-term securities that replaced them when they matured during the era of the Fed’s interest rate repression.

Retirees counting on their fixed income investments, such as CDs and bonds, for their supplemental cash flow have seen an even worse devastation of their cash-flows following the Fed’s interest rate repression that started in 2008.

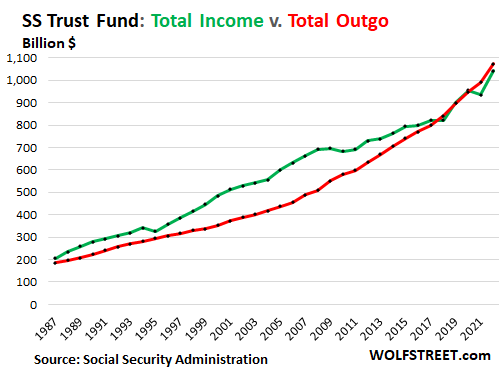

Gap between income and outgo narrows.

Total income from all sources (green line in the chart below) jumped by $105 billion from the prior year, to a record $1.04 trillion in the fiscal year ended in September because more people were working and they were earning higher wages and contributing more than during the pandemic year:

- Contributions jumped by $98 billion to a record $929 billion.

- Interest income fell by $5 billion to $65 billion (see chart above).

- Taxation of benefits rose by $13 billion to $47 billion.

Total outgo rose by $82 billion to $1.07 trillion (red line). Nearly all of it was in form of benefits paid.

The deficit (total income minus total outgo) of the fund narrowed to $32 billion, down from $55 billion in the prior year.

When the green line (total income) was above the red line (total outgo), the Fund accumulated assets. When the green line fell below the red line, the Fund shrank:

The costs of the Fed’s interest rate repression.

If the Fed hadn’t repressed interest rates since 2008, then interest payments would have roughly followed the increase in the Fund balance, and the Fund would have a surplus.

In 2010, the Fund earned interest at an average rate of 4.4%. In 2022, it earned interest at an average rate of 2.3%. If in 2022, the Fund still earned interest at an average rate of 4.4%, it would have collected $120 billion in interest, instead of $65 billion, and this additional $55 billion in interest income would have generated a surplus of $23 billion, instead of the $32 billion deficit. Yield investors around the country have gotten crushed even worse. Thank you, Fed!

Because the Fund invests in long-term securities – average remaining maturity is 6.2 years – and because interest rates of securities don’t change until the securities mature and are replaced with new securities, there is a lag of years before changes in long-term yields work their way into the “average interest rate” and into the interest-income stream.

Inflation, COLAs, and reality.

Social Security payments to beneficiaries are adjusted annually for inflation via “Cost of Living Adjustments” (COLA). The percentage of the COLA is the average CPI-W inflation rate in the third quarter, and is applied the following January for the whole year. The Social Security COLA for 2022 was 5.9%, the biggest since 1982. The COLA for 2023 will be 8.7%, the biggest since 1981.

The massive 5.9% COLA for 2022 was not nearly enough to overcome CPI inflation that raged at 8.2% for the 12 months through September. The 8.7% COLA has a better chance of at least matching CPI inflation in 2023. But there are no guarantees, and CPI inflation could still get worse.

Depending on where beneficiaries live and how they live, their actual costs of living may increase faster than the COLA.

Each year that the COLA falls behind actual costs-of-living increases, it affects all future years of benefits because inflation and COLAs are compounding, and that gap between them is compounding as well. Even small gaps year after year compound into big differences after 10 or 20 years.

In other words, if you think you’re comfortable living off your Social Security benefits when you retire, you will likely be squeezed 20 years later.

Depletion of the Trust Fund: whenever.

In fiscal year through September 2022, the gap between income and outgo narrowed to just $32 billion. This reduced the Fund less than expected. At this rate, which is unlikely, it would take 85 years to deplete the Trust Fund.

All predictions of how the next 10 years will work out – based on estimates for demographics, employment, wages, retirements, mortality, births, immigration, and the like – have been wrong in the past. They get adjusted up or down every year. No one knows. This year was better than expected. If there is a big recession next year, it will be worse than expected.

Several changes could put the Fund back on a growth track, likely a combination:

- Long-term interest rates stay in today’s range of 4.3% or higher for many years.

- Workers pay more, likely via a higher taxable maximum. It’s already indexed to inflation and will rise to $160,200 next year; it could be raised more than the inflation indexing.

- Full retirement age for future retirees could be delayed further but that poses lots of problems for people working in physical jobs and also due to age discrimination – when it’s impossible to find appropriate work.

- Benefits for future retirees, particularly the wealthiest, could be cut.

- The inflation measure for COLAs could be changed, such as replacing CPI-W with a chain-type price index, that will impoverish retirees in increments year after year, the most insidious way to cut benefits later in retirement when people can least afford it.

- Or a combination of them.

Note that long-term interest rates that prevailed before 2008 – before the Fed’s QE and interest rate repression – would eventually produce enough of a boost to interest income that it would go a long way toward overcoming the deficit in future years, and not a lot of other adjustments would have to be made to keep the fund balance growing. I’m rooting for the old normal interest rates.

Social security will be there, but it won’t be enough.

Retirees can rely on Social Security being there, but they should not rely on it as their only source of cash flow. Even if they can live off the benefits at first, they will find themselves in a tough spot as the COLAs are outrun in increments year after year by the rising costs of living that people actually face. This compounds over the years, and gets worse over the years.

Social Security wasn’t intended to provide comfortable retirement on its own, and it won’t. Some people move to a cheaper location in the US. Others move to cheaper countries, which works for a while and can be great fun. But the exchange rate could change to their disadvantage, and then the situation gets even more difficult.

For these reasons, it’s very important to build a sufficient nest egg during the working years. And it can be good for a host of reasons beyond money to extent the working years, even if it’s just with a part-time gig, maybe even something fun and interesting, that brings in some extra cash.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? Using ad blockers – I totally get why – but want to support the site? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()

[ad_2]

Source link