Least Geeky Explanation Ever of Differences Between CPI and PCE Price Index which the Fed Uses as Yardstick

OK, “least geeky ever,” I mean I don’t know that, but you get the idea. Fed governor Jefferson outlines the differences in a lecture at Harvard.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

I have long been covering and analyzing the Consumer Price Index (CPI), and its various sub-indices, released by the Bureau of Labor Statistics; and the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) Price Index, released by the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the entity that puts together the national accounts that go into GDP. The Fed uses the PCE price index as yardstick for its inflation targeting.

Both the CPI and the PCE price index dished up nasty surprises in January and December, driven largely by a jump in services inflation – and services are where the majority of consumer spending goes (here’s my discussion of CPI for January, note the spike in services inflation in the third chart; and here is my discussion of the PCE price index for January, note the spike in services inflation in the first chart).

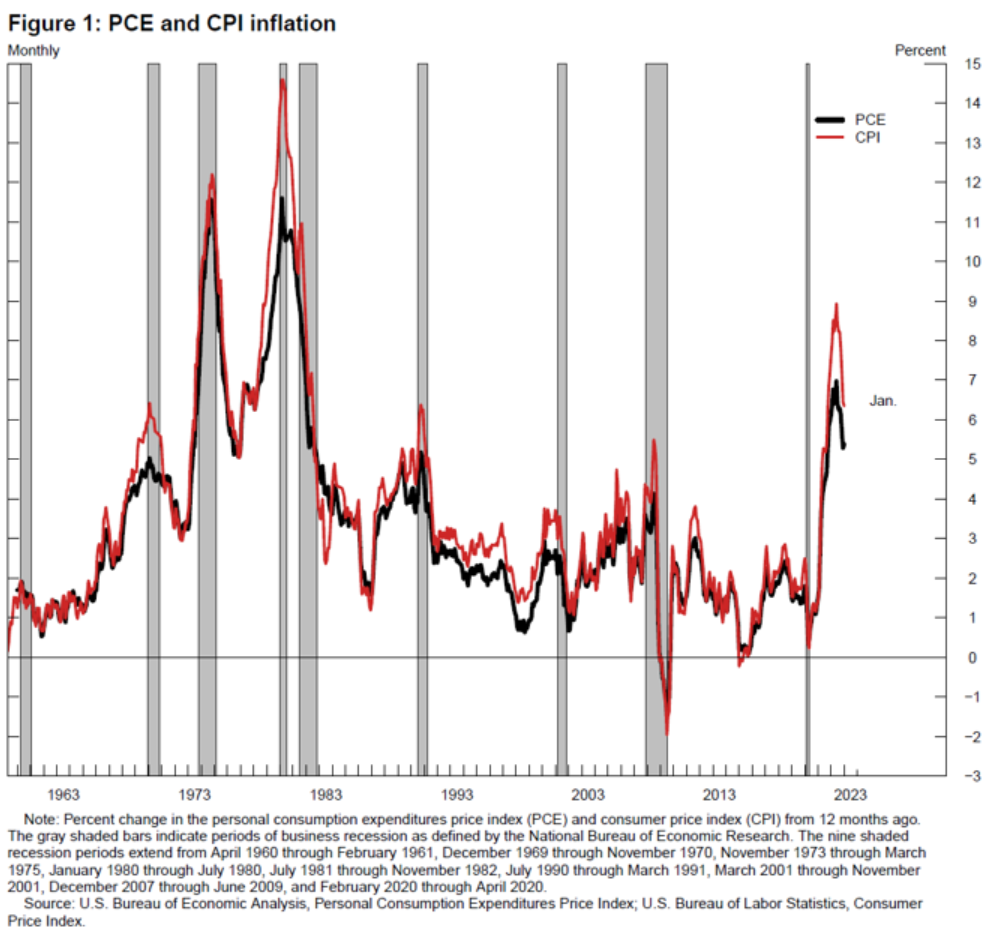

But there are big differences between the two indices, including that the year-over-year increases in the PCE price index are usually lower than those of CPI. This has to do with what data the indices draw from, their weights, and how the indices are constructed.

Fed Governor Philip Jefferson, speaking via video at a Harvard University economics class, outlined the differences in an easy-to-consume way. The lecture covered other topics as well, and was long. I will exclusively focus on the relatively brief discussion of the differences between CPI and the PCE price index (the entire lecture is here).

The below are excerpts from Fed Governor Jefferson’s speech, and the charts are from his presentation:

“Both indexes measure inflation using a specific basket of goods and services consumed by households. These baskets are similar but not identical across the two measures.

“Both measures also weight each item in their basket roughly in accordance with its expenditure share. That is, the more households spend on an item, like rent, the higher the weight it receives in the overall index. The weights are broadly similar across the two indexes, but, again, there are some important differences.

“First, the PCE price index has a broader scope than the CPI. The CPI is limited to expenditures that households pay out of pocket, while the PCE price index covers a broader set of goods and services as it seeks to cover prices for all consumer expenditures in the national income and product accounts (NIPA). For example, the PCE price index includes prices of the health services provided to households through Medicaid, while the CPI excludes these items.

“Second, the PCE price index and the CPI use different weighting systems. The PCE price index, which is more comprehensive than the CPI, estimates expenditure shares using the national income and product accounts, while the CPI measures expenditure shares using a separate survey of households, the Consumer Expenditure Survey. This leads to some differences in expenditure weights that can at times be important.

“For example, the share of medical services is notably higher in the PCE price index (partly because the PCE price index includes more kinds of medical expenditures), and the share of housing services is noticeably smaller (because overall expenditures are larger in the PCE price index). As a result, when health-care services or housing services inflation behave differently than other prices, this can lead to differences in PCE versus CPI inflation.

“Another difference in the weights is that the PCE price index uses time-varying weights, while the official CPI keeps weights fixed for a year. The PCE price index weights change to reflect changes in the goods consumers buy. For instance, at the start of the pandemic, the CPI was still giving the same weights to cruise ship and airline fares, even though no one was traveling.

[Here is my discussion on how the changed weights of CPI made CPI worse, with charts for the major CPI categories of their weights over time]

“The time-varying weights in PCE also account for substitution behavior. Suppose the price of apples goes up and the price of oranges stays the same. Consumers are then likely to substitute apples with oranges.

“In contrast, the CPI does not capture substitution behavior because the basket of goods consumers purchase is updated only once a year (instead of every month) and reflects expenditure patterns prevailing two years ago.

“The substitution effects captured by the PCE price index is one reason why PCE inflation (black line) is, almost always, lower than CPI inflation (red line), as you can see in figure 1. [Chart via Federal Reserve].

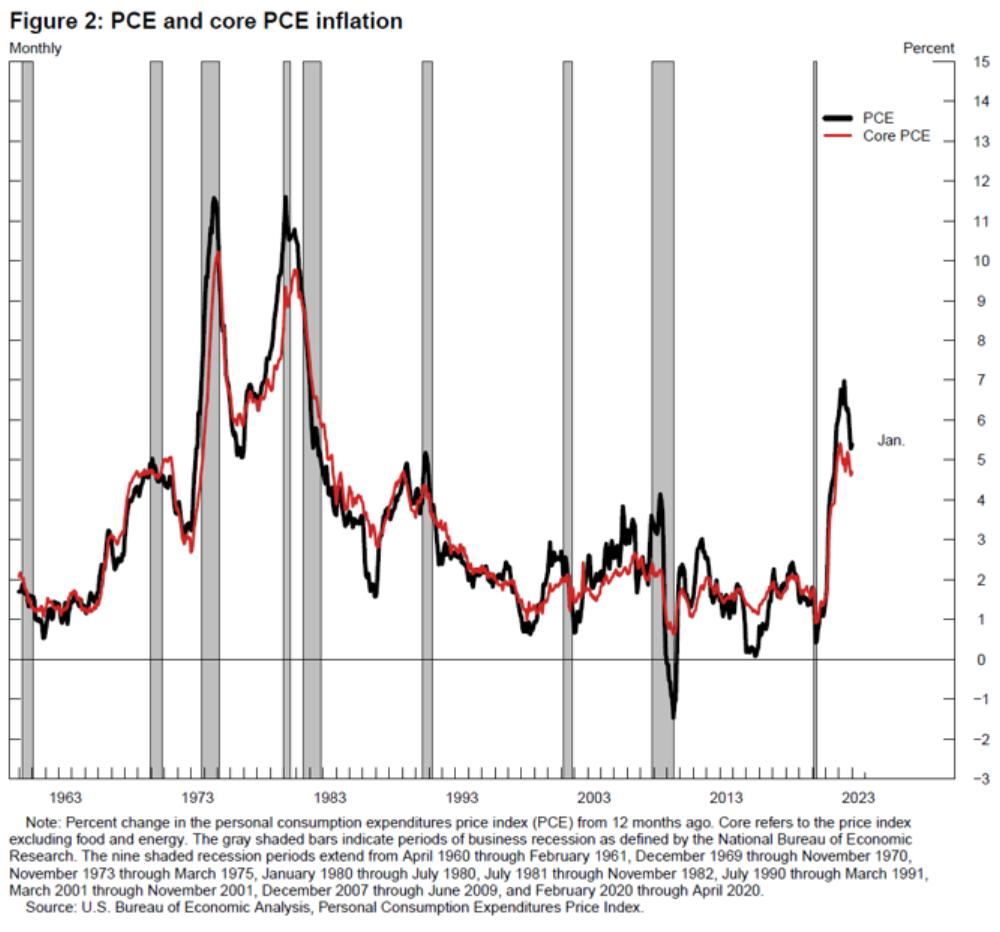

“As I mentioned earlier, there are both total and core PCE price and CPI indexes. The core subindex is the total index excluding food and energy prices. Food and energy prices are more volatile than other prices, which makes total inflation more volatile.

“This volatility is evident in figure 2. You can see the black line (total PCE price index) exhibiting more drastic ups and downs than core PCE price index, the red line in the graph, and many of the sharp movements are short lived. In other words, the volatility in the total PCE price index makes it harder to discern trends (longer-lasting movements) from transitory movements.

“In addition, food and energy prices often depend on factors that are beyond the influence of monetary policy, such as geopolitical developments (for example, those associated with fluctuations in energy prices) or weather or disease or war (for example, in the case of food prices). [Chart via Federal Reserve].

“In summary, the differences between CPI and PCE price indexes are important. The FOMC has chosen to target the PCE price index because it is broader and it captures more accurately what households are actually consuming. In addition, food and energy account for a significant portion of household budgets, so the Federal Reserve’s inflation objective is defined in terms of the total PCE price index, but the Fed monitors the core PCE price index, as well as other inflation indicators, in order to identify evolving inflation trends.”

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()

[ad_2]

Source link