Six-Month Treasury Yield Begins to Price in One More Rate Hike

Either mid-June or possibly in July.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

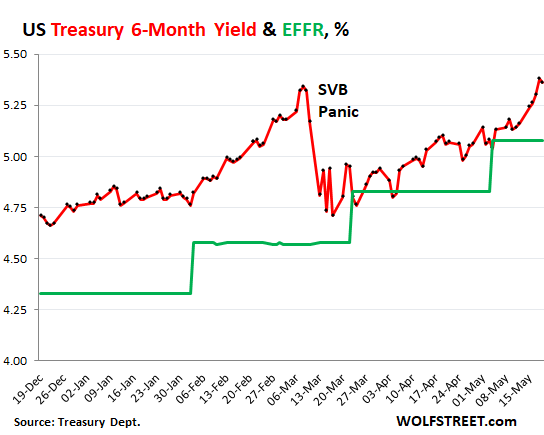

Treasury yields and mortgage rates rose essentially all week and passed some milestones for the first time since the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank:

- The six-month yield hit a 22-year high (5.38%)

- The one-year Treasury yield edged above 5%

- The 10-year Treasury yield rose to 3.7%

- The 20-year Treasury yield edged past 4%

- The 30-year Treasury yield rose to nearly 4%

- The average 30-year fixed mortgage rate rose to 6.90% (Mortgage News Daily).

But what is really interesting is the action in the six-month yield (securities that mature in November): Buyers and sellers in this section of the bond market got over their bank-panic and now are starting to price in another rate hike.

The six-month yield now prices in one more rate hike.

The six-month yield closed at 5.36% on Friday, after the 5.38% close on Thursday, both the highest closing yields in 22 years (January 2001), having now entirely shaken off the spooky collapse of Silicon Valley Bank.

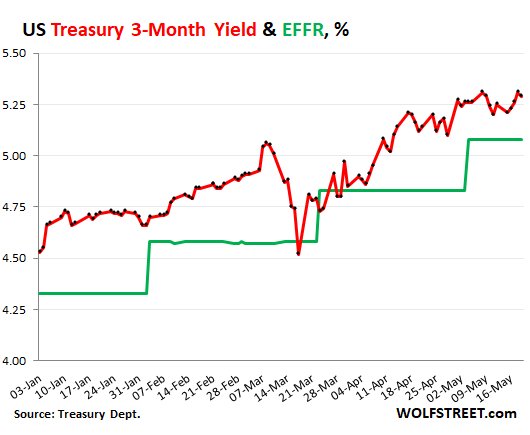

The effective federal funds rate (EFFR), which the Fed brackets within its target range between 5.0% and 5.25%, has been at 5.08% since the last rate hike. Another 25-basis point rate hike would bring it to 5.33%. That additional rake hike would put the EFFR just below where the six-month yield is already today.

The part of the bond market that is trading the six-month maturities, after calming down from the bank panic and then re-reading the tea leaves that the Fed put out there, is now starting to see another rate hike over the next few months – if not in June, then at one of the following meetings. And it is getting ready for that rate hike and is starting to price it in. That’s what the six-month yield shows.

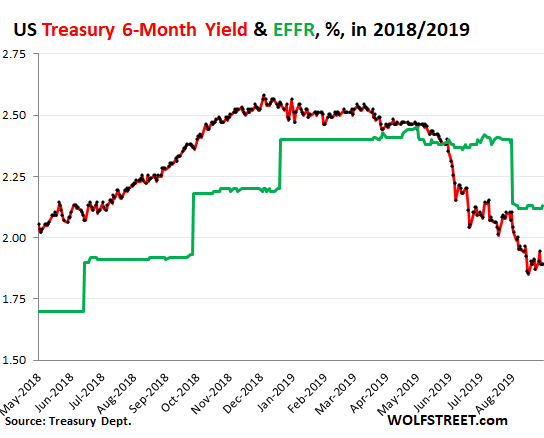

To compare: End of last rate-hike cycle in 2018-2019.

The last rate-hike cycle was a timid affair. But inflation was mostly below the Fed’s 2% target (core PCE price index), and occasionally hit the Fed’s target, but never seriously swerved above the 2% line. The Fed was hiking rates to “normalize” monetary policy, not to fight inflation.

It started with one hike in December 2015, another hike in December 2016, three in 2017, and four in 2018, each hike a basic 25 basis points.

By 2018, stocks were tanking, real estate started to lose ground, and President Trump keelhauled Chair Powell (whom he’d appointed) on a daily basis because of the rate hikes and QT. By late November and early December, Fed governors were alluding to eventually ending the rate hikes. At the December FOMC meeting, the Fed hiked one more time and signaled that the rate hikes would be over.

Even before the December 2018 meeting, the six-month yield started edging lower. It peaked at 2.58% on December 4, and by the time of the FOMC meeting on December 19, it was at 2.54%, and then began heading lower gradually over the following months, while the Fed kept policy rates unchanged.

By early June 2019, when the Fed was signaling rate cuts, the six-month yield fell below the EFFR and started pricing in the first rate cut, which it had fully priced in by mid-June. The rate cut came on August 1:

The six-month yield reflects securities that mature in November, and the debt-ceiling turmoil doesn’t impact it. That turmoil and the risk the US might default in June has thrown the one-month yield into utter chaos though.

The part of the bond market that is trading in long-dated securities is often hilariously wrong. Remember when it took the 10-year yield down to 0.5% in August 2020, betting on the 10-year yield going negative as it had already done in Europe.

Banks, which are a big part of the bond market, believed this nonsense too, and they loaded up on long-dated bonds and MBS, and then when yields began to rise in reaction to the first signs of big inflation, banks doubled down, believing the Fed’s nonsense about inflation being “transitory,” and when the Fed ate its words and started hiking rates, they continued to buy long-dated bonds instead of dumping them, and then several of these banks collapsed because of their stupid decision to pile into long-dated securities as inflation was rising. So that’s part of the long-dated bond market.

But the other end of the bond market is trading short-term, with securities that mature over the next few months to a year. And they watch what the Fed is actually doing, and they listen to the short-term guidance the Fed gives through its policy decisions, the press conferences, the meeting minutes, and the countless speeches Fed governors give. And by the time the rate hikes or rate cuts take place – unless they’re a surprise – the short-term yields have already mostly or totally priced them in.

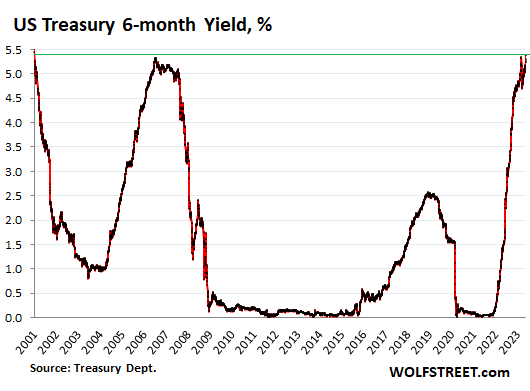

The six-month yield now highest in 22 years:

The six-month yield on Thursday at 5.38% and on Friday at 5.36% is now at the highest level since January 2001, having edged past the 5.34% of March 8. A 22-year record is something to celebrate, no?

The three-month yield, after the bank panic, also reads the tea leaves and gets on board:

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()

[ad_2]

Source link