Central Banks To Step Back As Inflation Steps Up

Authored by Simon White, Bloomberg macro strategist,

Rising global rate expectations are likely to be disappointed as slowing inflation significantly tightens real rates through the rest of the year, allowing central banks to deliver fewer hikes than priced.

After a slew of central-bank surprises, in Canada, Australia and the UK, and Wednesday’s “hawkish pause” from the Federal Reserve, you’d be forgiven for thinking we’re in a re-invigorated monetary-tightening regime.

But not only are global financial conditions in fact continuing to loosen, central banks’ hawkish handiwork will be amplified in the coming months by slowing inflation, allowing them to limit further rate rises, and leading to the likelihood rate expectations around the world are overdone.

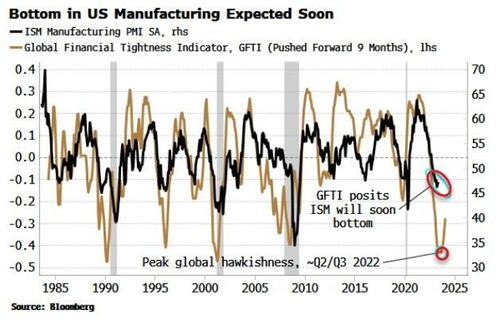

A very simple and elegant way to measure global hawkishness and the tightness of financial conditions is to count the number of central banks who are raising rates – this is in essence what the Global Financial Tightness Indicator (GFTI) captures.

In the chart below we can see the GFTI bottomed around the second or third quarter last year, marking peak global hawkishness. Financial conditions, perhaps contrary to intuition, have in fact been loosening since then.

The GFTI is not an abstract concept, it says things about the real economy. The looser conditions it indicates posits that a bottom is near at hand for the highly-cyclical US manufacturing sector.

A US recession is very likely, but what this forward-looking framework shows is that manufacturing – one of the first sectors that went into a recession – is likely to be one of the first out of it.

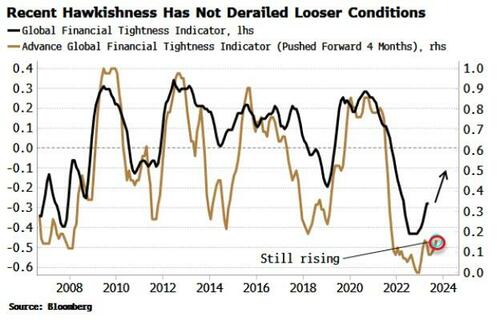

We can take the GFTI one step further by constructing the Advanced GFTI, based on central bank rate-hike expectations.

This shows that the recent hawkishness in the UK, Canada and Australia has not been enough to significantly alter the message from the Advanced GFTI that financial conditions should keep loosening.

The same message of looser conditions is coming from excess liquidity, the difference between real money growth and economic growth.

Despite rates at decade highs and contracting central-bank balance sheets, excess liquidity is in fact rising, providing a tail wind for risk assets such as stocks and commodities.

This leaves a paradox. If financial conditions are loosening, why would central banks not turn much more hawkish?

-

Firstly, monetary policy makers focus not on leading data, but on data that heavily lags, such as inflation and growth. Both are falling as the cycle draws to a close, which will induce the Fed et al to ease back on tightening until they can see the full effect of their previous rate increases.

-

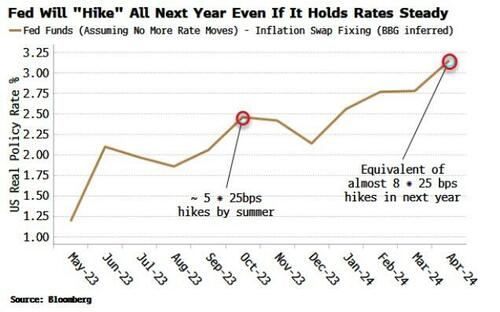

Secondly, as mentioned above, slowing inflation will tighten monetary policy even if central banks hold rates steady. We are in a clear disinflationary trend, and headline inflation should keep falling through the rest of the year.

Longer-term inflation forecasts are tricky and often wrong, but over the next 3-6 months it is possible to make much more accurate predictions, based on a nuanced view of the construction of the consumer basket, and the impact of base effects. Inflation-fixing swaps are probably the best near-term forecast of monthly CPI prints as they come from inflation traders who have real money at stake.

Take the US. CPI-fixing swaps there show that even if the Fed holds rates steady, slowing inflation ensures the real rate will rise the equivalent of five more rate hikes by the late summer, or eight by next April.

We will see this in many other places too, such as Europe and the UK, as falling energy prices continue to ensure headline inflation numbers keep slowing for now.

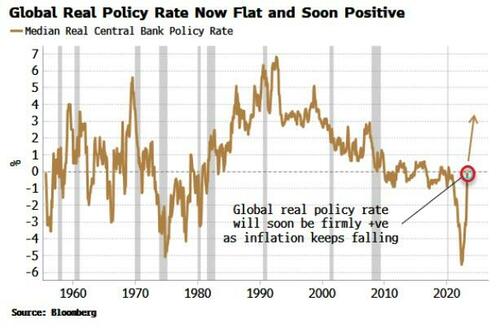

Crucially, central banks have already made significant progress in tightening monetary policy, with the global real policy rate now back to neutral after reaching record negative levels.

This shows the banks have already done a lot of the heavy lifting, and now the mechanical effects of slowing inflation will take on the tightening burden, soon taking the global real rate significantly positive, and therefore more restrictive.

The Fed is a case in point, with the loud hawkish rhetoric at Wednesday’s FOMC “out-decibeled” by the unmissable fact that it kept rates on hold.

The banks can therefore afford to step back. And the sooner they pause – and the longer – the more likely it morphs into a rate cut as the economy weakens further.

Thus a good proportion of the ~290 bps of rate hikes priced in between the US, Canada, Europe, the UK, Australia and New Zealand by the end of the year are liable to be unrealized.

Slowing inflation may be the friend of central banks through the rest of the year, but it will prove to be the foe of anyone looking for higher shorter-term nominal rates.

Loading…

[ad_2]

Source link