Interest Payments on the Ballooning Federal Debt vs. Tax Receipts & GDP: Not as Bad as in 1982-1997, but Getting There

Our drunken sailors in Congress better head to the detox.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

The magnificently ballooning US government debt is rapidly approaching $34 trillion (now at $33.84 trillion), up from $33 trillion in mid-September, and up from $32 trillion in mid-June, amid a tsunami of issuance of Treasury securities to fund the stunning government deficits.

But inflation has broken out on a massive scale in early 2021, and the Fed has hiked its policy rates to 5.5% at the top end, and it has unloaded $1.1 trillion from its balance sheet under its QT program, which is pushing up long-term yields. And so the interest rates that the Treasury Department has to pay to be able to sell these mountains of Treasury securities every week has risen, with T-bills selling at yields of around 5.5% and longer-term securities selling at yields in the 4.3% to 4.7% range, after going over 5% a month ago.

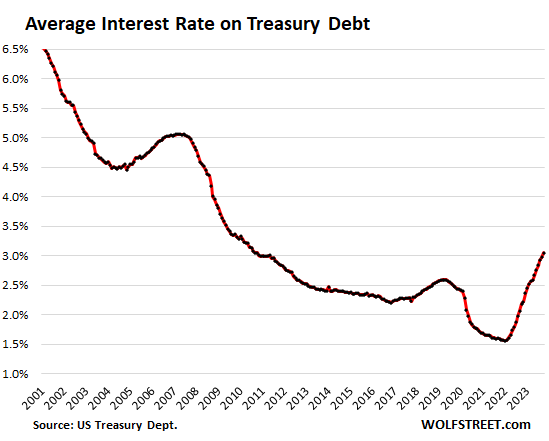

So the average interest rate that the government is paying on all its interest-bearing debt – much of it issued years ago with much lower coupon interest rates than now – has been rising from the historic low of 1.57% in February 2022 to 3.05% in October, according to data from the Treasury Dept.

This average interest rate will continue to rise as new securities with higher interest rates replace maturing lower-interest rate securities that were issued often years ago, and as all the newly added debt is piled on at the current higher interest rates.

The securities issued recently will cost the government whatever coupon interest they came with until they mature. The $40 billion of 10-year Treasury notes that were sold at the November 8 auction with a yield of 4.52% will cost the government 4.5% in coupon interest payments for the next 10 years, no matter what happens to interest rates.

The interest burden gets heavier. How heavy?

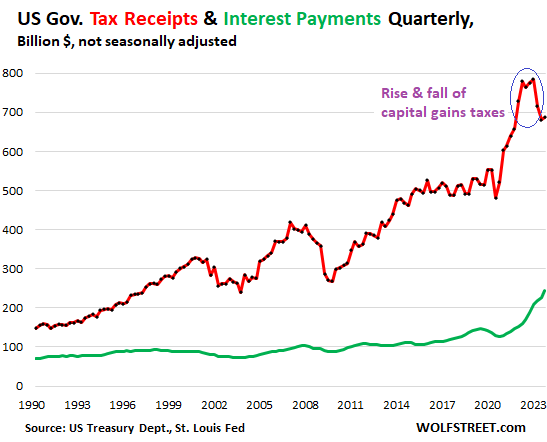

Interest payments reached $245 billion (not seasonally adjusted) in Q3, having doubled since 2018. But the economy has grown a lot, employment has grown, a record number of people are working, and they’re earning record amounts of money, and they have received the highest pay increases in 40 years, and inflation has taken off, and corporate profits have ballooned, and there were huge capital gains in 2020 and 2021, all of which triggered massive amounts of tax receipts.

In 2022, markets handed investors a crappy deal, and capital-gains tax receipts in Q1 and Q2 this year for the tax year 2022 plunged, even as other income taxes continued to surge. And these tax revenues have to be used to pay for the interest on the debt.

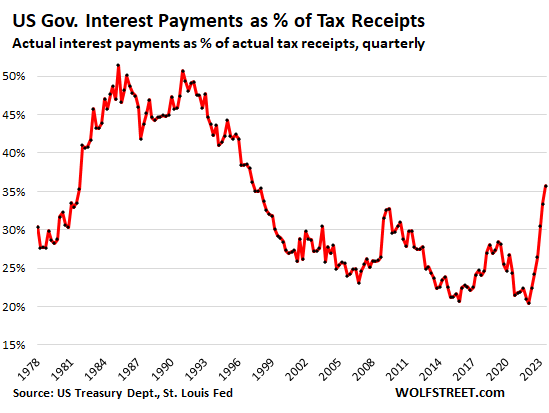

Interest payments as % of tax revenues is the primary measure of the burden of the national debt on government finances. This measure of tax revenues – total tax revenues minus contributions to Social Security, other social insurance, and some other factors – was released today by the Bureau of Economic Analysis as part of its GDP revision. This portion of the tax revenues is what’s available to pay for regular government expenditures, including interest expense.

The ratio of interest expense as percent of tax revenues spiked to 35.7% in Q3, up from 24.3% a year ago, and back where it had been in Q2 1997. But:

- The spike was from the 20.4% in Q1 2022, the lowest since 1969.

- In the 15 years between 1982 and 1997, the ratio was higher.

- In the 10 years between 1983 and 1993, the ratio ranged from 45% to 52%.

Tax revenues (minus contributions to Social Security, other social insurance, and some other factors) rose to $687 billion in Q3, after having dropped in Q1 and Q2 on plunging capital-gains tax revenues following the crappy year 2022 for stocks, bonds, cryptos, and other investments.

The plunge of the capital gains taxes was off the top of the Fed-fueled asset-price spike in 2020 and 2021 (red line in the chart below).

Interest payments jumped to $245 billion in Q3, on the ballooning debt funded with higher average interest rates (green).

This chart puts into perspective the interest payments and the tax revenues (minus contributions to Social Security, other social insurance, etc.) that are available to make those interest payments.

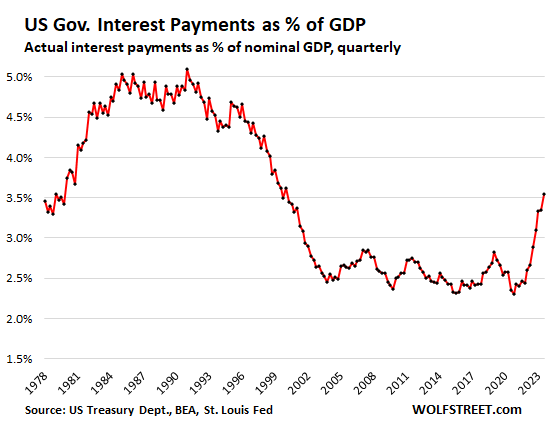

Interest payments as percent of GDP rose to 3.5% in Q3, based on today’s revised nominal GDP for Q3.

The ratio is figured on an apples-to-apples basis: quarterly interest expense not adjusted for inflation, not seasonally adjusted, not annual rate; divided by quarterly nominal GDP ($6.93 trillion in current dollars) not adjusted for inflation, not seasonally adjusted, not annual rate.

The ratio of 3.5% was the highest since 2000, but well below the range between 1979 and 2002, when it had peaked at over 5%, and stayed above 4.5% for nearly 15 years.

So, this is a gruesome spike, but off very low levels, and not yet in the nightmare territory of the 1980s. But at the current rate of progress, the spike might reach those nightmare levels in a couple of years.

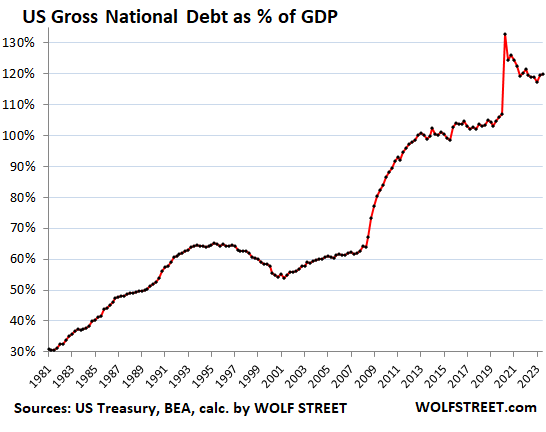

The US national debt-to-GDP ratio rose to 120% in Q3. So this measure is not impacted by interest payments or interest rates. This is the total gross national debt at the end of Q3 (not adjusted for inflation) divided by nominal GDP (seasonally adjusted annual rate, not adjusted for inflation).

The spike in Q2 2020 to 133% had occurred mostly because GDP had collapsed, and to a lesser extent because the debt had jumped.

If nominal GDP grows faster than the debt, the ratio declines, and therefore the burden of the debt declines, as it has done after Q2 2020.

But in Q3, nominal GDP grew by 2.1% from the prior quarter (not annualized, not adjusted for inflation), while the debt grew by 3.5% over the same period (also not annualized, not adjusted for inflation). And so the burden of the debt grew. A similar thing happened in Q2.

High interest burden might send Congress into Detox, but not yet. Back in the 1980s through early 1990s, the issue of interest expense eating half of the federal tax revenues (minus social insurance), while bond vigilantes were trotting around nervously, triggered a lot of handwringing in Congress and eventually forced Congress to begin grappling with reality. Eventually, they brought down the deficits.

High interest burden might be the only discipline left that can push our drunken sailors in Congress into detox to sober up. But it’s not happening yet. Our drunken sailors in Congress – “our” because we put them there, and we give them the booze – are still partying, and they’re brushing off the grandstanding about the debt in some corners.

The Fed’s role in this fiasco. With its reckless interest-rate repression from 2008 through 2021, via near-0% policy rates and trillions of dollars in QE, the Fed has encouraged Congress to go on an epic deficit-spending binge because the debt doesn’t really matter when the cost of borrowing is near zero. Now it suddenly matters, and it will matter a lot more going forward.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()

[ad_2]

Source link