The European Central Bank only stopped its most aggressive ever series of interest rate increases in October. But already pressure is mounting from investors to start lowering borrowing costs.

When the ECB governing council meets in Frankfurt on Thursday, it is expected to leave rates unchanged, even though eurozone inflation is falling much closer to its 2 per cent target.

Rather than consider relaxing policy, the central bank is instead preparing to push back against market bets on a cut as early as March by pointing out they still see upside risks on prices, particularly from rising wages.

With official forecasts for eurozone growth and inflation expected to be cut and investors watching for any clues on when rates may be reduced, these are the main questions for the ECB:

Are rate-setters behind the curve on falling inflation?

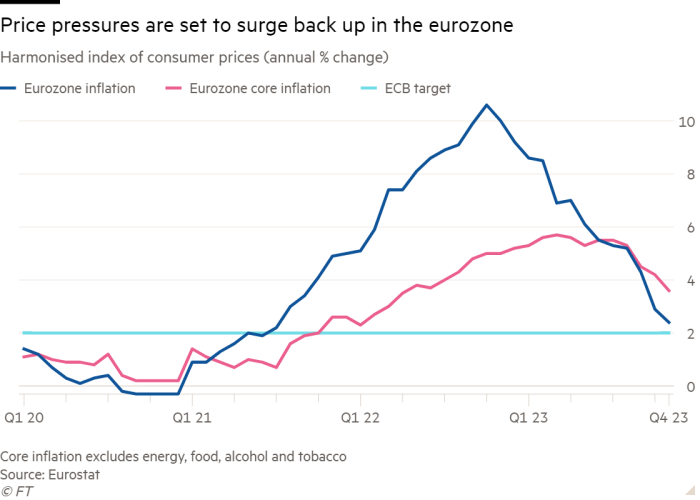

Eurozone inflation has been slowing throughout 2023, as energy prices retreated from last year’s surge caused by Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Yet ECB policymakers have continued to warn of the risk that price growth could yet get stuck above its 2 per cent target.

However, this scenario of the “last mile” of disinflation being the hardest looks much less likely after euro area inflation dropped to 2.4 per cent in November — far lower than expected and tantalisingly close to target.

Given the ECB forecast in September that inflation would remain above 3 per cent until the fourth quarter of next year, monetary policymakers seem to have underestimated the pace of disinflation. Krishna Guha, vice-chair of Evercore ISI, said: “The data suggests the ECB has overtightened.”

Deutsche Bank economists expect the ECB on Thursday to cut its 2024 forecast for core inflation — which excludes energy and food to give a better picture of underlying price pressures — from 2.9 per cent to 2.1 per cent.

Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, a former ECB executive who now chairs French bank Société Générale, said that after badly underestimating the rise of inflation last year, central bankers “may once again be late in adjusting their policies” as price pressures fade.

Is the market right that rate cuts are imminent?

Isabel Schnabel, the most hawkish member of the ECB board, signalled last week that the “encouraging” fall in inflation had shifted sentiment among policymakers by repeating a quote often attributed to John Maynard Keynes: “When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?”

But the only concrete change in Schnabel’s position is that she no longer thinks a rate rise is still a realistic possibility. She was careful not to discuss the timing of cuts and stressed the central bank had to be more cautious than the market. “We still need to see some further progress with regard to underlying inflation,” she said. “We must not declare victory over inflation prematurely.”

Inflation is expected to bounce back up again to near 3 per cent in December as German energy prices will rise from a year ago when the government paid most households’ gas and electricity bills, according to the Bundesbank.

“That rebound in inflation will give the ECB some breathing room before they need to cut,” said Frederik Ducrozet, head of macroeconomic research at Pictet Wealth Management, adding he thinks rate cuts could start in April. “Having failed to appreciate the rise in inflation two years ago, it is natural they are reluctant to declare victory too early.”

What could prevent rate cuts in March?

Wages are the biggest factor. Eurozone unit labour costs per hour worked rose 6.8 per cent in the third quarter from a year earlier, the fastest pace since Eurostat records started in 1995. Daniel Vernazza, an economist at Italian bank UniCredit, said this rise reflected “a fall in labour productivity — strong employment and weak output — and high wage growth”.

ECB president Christine Lagarde said last month she still wanted to see “firm evidence” that tight labour markets were not causing another inflationary surge.

Wages are a key input to prices for labour-intensive services, which make up 44 per cent of the euro area inflation basket and are still rising at an annual rate of 4 per cent. The ECB will want to see the results of collective bargaining agreements with unions in early 2024 and a further squeezing of profit margins to judge if services prices will continue to slow.

“They are likely to say there is more work to be done,” said Konstantin Veit, a portfolio manager at investor Pimco. “Core inflation is still at 3.6 per cent in the euro area, the ECB needs unit labour costs and profit margins to come down in line with its target and the jury is still out on this, so they will wait to have more clarity next spring.”

Will the ECB stop buying bonds early?

The ECB ended much of its bond-buying last year. But it is still reinvesting the proceeds of maturing securities in the €1.7tn portfolio it started buying in response to the pandemic. It has set out plans to continue these reinvestments until at least the end of next year, which would entail buying some €180bn of bonds in 2024.

Several of the more hawkish members of the ECB have called for these reinvestments to end early. Lagarde said last month the matter would be discussed “in the not too distant future” and many observers expect it to start reducing the purchases as early as April.

Schnabel said it did not seem “such a big deal” because these purchases were going to end anyway and the amounts are “relatively small”.

But some policymakers say the flexibility to focus ECB reinvestments on any country is useful to counter a potential surge in borrowing costs for a highly indebted country like Italy.

“It is not clear why the ECB has brought up this topic of ending reinvestments early — it risks incoherence with the shift towards cutting rates,” said Katharine Neiss, a former Bank of England official who is now chief European economist at US investor PGIM Fixed Income.