Gold shows its mettle: In a world of cryptocurrencies and AI stocks, investors still drawn to the oldest commodity

The past few months have seen an unexpected surge in the price of gold, a commodity that has done exceedingly well despite a series of unfavourable conditions.

Closing at an all-time high in December, gold prices neared $2,100 (€1,950) per ounce and in defiance of traditional economic theory, grew 15% in 2023.

Initially forecasted to yield returns of just 2%, gold ended last year as one of the best-performing assets despite what interest rates and inflationary conditions led many forecasters to believe.

Like any commodity, gold prices are impacted by many factors, one of the most important being real interest rates which is the opportunity cost of holding yield-free bullion.

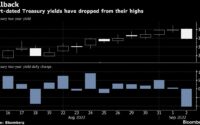

But while yields on 10-year inflation-protected bonds have come down from their peak of 2.5% in October, they remain at highs not seen since 2009.

In addition, the last 18 months have seen central banks raise interest rates like never before as part of an aggressive attempt to tame inflation, with the current rate environment marking one of the highest seen in decades.

The European Central Bank (ECB) raised interest rates 10 times across 14 months, by a total of 450 basis points.

Currently, the ECB’s main refinancing rate is 4.5% and while the door to reducing rates has been opened, policymakers remain hesitant to provide clear guidance on when monetary policy should be loosened.

In the US, chair of the Federal Reserve Jerome Powell has also kept the timing of its first-rate reduction close to his chest. Since March 2022, the Fed has raised rates 11 times, with its benchmark lending rate of 5.25%-5.5% now at a 23-year high.

Yet despite interest rates being so high, gold prices have taken off, bringing what should be an inverse relationship into question.

“The surprising thing is how well gold did considering how high interest rates went,” says Fergal O’Connor, senior lecturer in financial economics at University College Cork and expert adviser to the World Gold Council.

“Normally, if you asked me what would happen if interest rates went from where they were in 2020 to where they are now, I would assume that gold would be down around $1,200-$1,300, all else being equal. Instead, it has held above $2,000.”

At the same time, inflation — which, when high, results in increased demand for gold — has fallen dramatically from post-pandemic surges of over 10%, with latest figures on the eurozone reporting price level increases of just 2.8%. Similarly, US inflation is predicted by the OECD to drop to just 2.2% in 2024 as prices among core items continue to stabilise.

Yet, while price levels follow a path of post-pandemic recovery, bullion, which is commonly used as a hedge for rising inflation, has reached new highs, contrary to tradition.

So, with interest rates at a two-decade high and inflationary pressure dampening, why have gold prices taken off?

“Gold has value because of central banks, that’s what makes it different to everything else,” says Mr O’Connor.

“The big surprise last year was how well gold did because it looked like it would suffer. But, for two years in a row, central banks have bought over 1,000 tonnes of gold, which is well above their average of somewhere between 200 and 300.

“That is a huge amount to buy when you think that gold mining adds about 3,500 tonnes a year. They’re buying up well over a quarter of newly mined gold.”

One such bank is our own. In 2022, the Central Bank of Ireland doubled the amount it owns in gold reserves, increasing its holdings from six metric tonnes to 12.

At the time, then finance minister Pascal Donohoe said the Central Bank increased its holdings as part of a “diversified longer-term investment strategy for the discretionary investment assets, aimed at improving balance sheet resilience”.

While uncommon for individual banks to elaborate on trading decisions, findings from the World Gold Council point to three key reasons for a rise in gold purchasing.

In the Central Bank Survey published last year, the organisation noted that the rationale to increase gold holdings came as “no surprise”, with interest rate levels, inflation concerns, and geopolitical risks comprising the three leading factors in central bankers’ reserve management decisions.

In addition, 70% of banks surveyed believed gold reserves would continue to rise in the next 12 months, reflecting a 10-point increase from the previous year.

“The scary beast for gold next year is what the Central Banks do,” says Mr O’Connor.

“With geopolitics the way that it is, I think it is safe to say they will keep on buying, but if they take their foot off the pedal by even half, that leaves a lot for someone else to buy.”

Yet, despite their significance in influencing gold prices and the impact they had over the past 12 months, central banks account for just 15% of total global gold ownership.

While this far exceeds the 9% share of bullion used solely for investment purposes, both are trumped by an invisible elephant in the room, which is genuine consumer demand for the precious metal.

“Gold doesn’t make sense as a pure financial asset, but that is because it isn’t one,” Mr O’Connor explains.

“Since 1970, nominal world GDP has grown by about 7% per year. Gold has also grown roughly by 7% a year. That doesn’t make sense for many people because they see gold as just financial, but 70% of all the gold in the world is held in jewellery, bar and coin, and most of its demand comes from ordinary people.

“When people try to work out why gold is valuable, there are only two real reasons; because central banks own it, and people want it for adornment purposes.

On a really silly level, this is simply about supply and demand.”

While short-term relationships between gold and interest rates may have proven futile, annual jewellery consumption held steady throughout 2023, even in a very high-price environment, according to the World Gold Council, with demand driven largely by a recovering Chinese economy and a growing Indian market.

So while 2023 has done little to support the relationships between short-term determinants and gold prices, what it has done is highlight the significance of the silent majority, those who buy gold just to have it, along with central banks who fear what may happen if they don’t.

So, what does this mean for 2024? The World Gold Council expects central banks to keep buying at an impressive rate while at the same time signalling the start of rate cuts come mid-year.

“The 70% of gold owned by consumers is not being traded day-to-day and the demand in this segment is least likely to change,” says Mr O’Connor.

“That, coupled with continued central bank purchases and falling interest rates, I think we’re looking at a good year.”

[ad_2]

Source link

Related Posts

US credit squeeze triggers rise in corporate bankruptcies

Existing Home Sales Fall for 10th Straight Month as Housing Bubble Continues to Deflate