Deep-Subprime & Subprime Auto Loans Miraculously Cleaned up by Credit-Score Inflation

Credit-score inflation throws a monkey wrench into the calculus of credit risk.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

A miracle in American consumerism happened during the pandemic, the era of mortgage forbearance, student loan forbearance, and rent moratoriums, and free money sent to consumers via stimulus checks and PPP loans: credit score inflation.

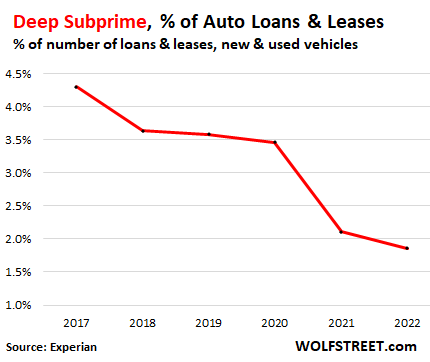

Of the total number of auto loans and leases outstanding in Q2, the share of borrowers with “deep subprime” credit ratings (credit scores of 300-500 on Experian’s credit score scale) plunged from 4.3% in 2017 to a share of only 1.9%, according to Experian’s State of the Automotive Finance Market report for Q2 2022.

This means that the majority of deep-subprime borrowers with auto loans improved their credit scores and moved into higher categories. For example, a deep-subprime borrower might have improved their credit score from 450 to 520, thereby moving up into subprime.

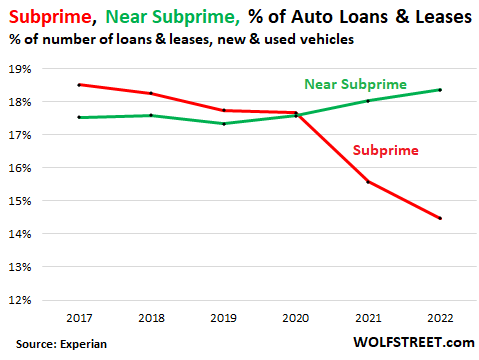

Of the total number of auto loans and leases outstanding, the share of borrowers with “subprime” credit ratings (credit scores of 501-600) has dropped from 18.5% in 2017 to a share of 14.5% in Q2 2022 (red line in the chart below). This means that many subprime borrowers improved their credit scores and moved into higher categories.

As you’d expect, the share of “near subprime” (credit score of 601-660), that many subprime borrowers and some deep-subprime borrowers moved into, rose from 17.5% in 2017 to a share of 18.4% in Q2, according to Experian (green line in the chart below).

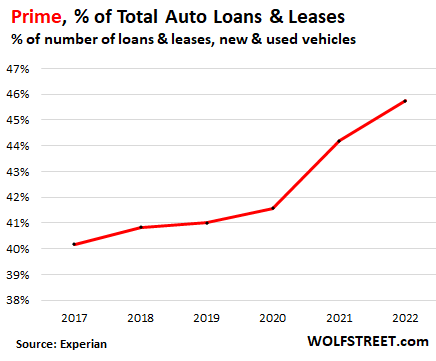

Of the total number of auto loans and leases outstanding, the share of borrowers with “prime” credit ratings (credit scores of 661-780) jumped from 40.2% in 2017 to a share of 45.7% in Q2 2022, as many near-subprime and subprime borrowers moved up into this category.

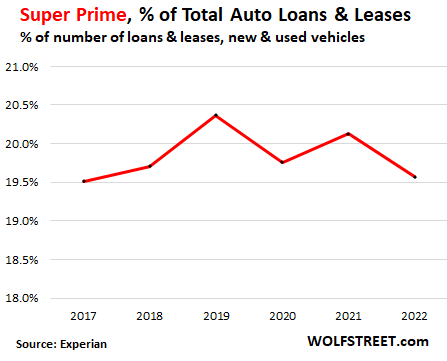

But the share of “super prime” borrowers (credit scores of 781-850) has been roughly flat with 2017:

An amazing miracle. But how did it happen?

Student loan forbearance. Starting in March 2020, all federal student loans were automatically enrolled in forbearance programs. Loans in forbearance no longer count as “delinquent,” no matter how delinquent they were. And the delinquency rate of federal student loans plunged from around 10% in 2019 to 0%.

In other words, as far as the credit ratings are concerned, those delinquencies among federal student loans were cured, and it improved borrowers’ credit scores, though they didn’t actually make any payments.

Private student loans didn’t participate in the forbearance, and the delinquencies still out there are concentrated among them.

In addition, since these student loans in forbearance were on ice, not accruing interest and borrowers not making payments, borrowers could use the money from the not-made loan-payments to get caught up on other bills, which would further improve their credit scores.

The federal student-loan forbearance program has been extended through December 31, 2022.

Mortgage forbearance. Same principle here. Millions of home mortgages were entered into forbearance programs. Delinquent mortgages in forbearance didn’t count as delinquent, which cured the delinquency on the credit reports.

In addition, borrowers didn’t have to make mortgage payments during the forbearance period and could spend the money on other stuff, such as getting caught up with their other debts and curing those delinquencies.

Most of the mortgages have now exited forbearance, and given the surge in home prices over the period, as a last resort, borrowers could usually sell the home and pay off the mortgage.

Rent moratoriums allowed renters to divert funds from rent payments to other causes and catching up with their bills and car payments.

In addition, waves of government cash, from stimulus payments to PPP loans, washed across the US, allowing people to get caught up on their debts.

As a consequence, delinquency rates plunged to record lows during the pandemic across auto loans, credit cards, mortgages, student loans, and other consumer loans. Third-party collections and bankruptcies also plunged to record historic lows. And credit scores began to surge.

Credit-score inflation throws a monkey wrench into credit risk calculus.

But credit scores didn’t improve because American borrowers suddenly became vastly more responsible. They improved because of the dynamics that cured delinquencies on credit reports.

But those dynamics were pandemic-specials that cleaned up the credit reports of millions of Americans that now appear to have made their payments on time, and appear to have caught up on their payments, when in fact it was mass-forbearance that produced that effect, along with stimulus payments that aren’t scheduled to recur.

And that’s a problem for lenders. Lenders use credit reports and credit scores to evaluate the credit risk of a borrower – how likely they are to default on their debts in the future. The assumption is that past delinquencies are predictors of future delinquencies.

Lenders charge higher interest rates to compensate them for higher credit risks. Subprime rated customers borrow at higher rates than prime-rated customers because lenders face a higher risk of credit losses – similar to corporate junk bonds. But credit-score inflation is now throwing a monkey wrench into the equation and turning the already iffy credit score system into an even less reliable predictor of credit risk.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? Using ad blockers – I totally get why – but want to support the site? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()

[ad_2]

Source link