Keeping an Eye on the Labor Market to See if the Fed’s Anti-Inflation Drug Started Working

Maybe just a little. But not seeing the Great Loosening of the job market yet. Laid-off H-1B visa holders complicate the picture.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

The Fed is using a wide range of labor market data as indication of how its anti-inflation medication is working, as we know from Powell. Amid all these tech layoff announcements, we’re going to keep our eyes on the most immediate and raw data on the labor market that we have – weekly unemployment insurance claims – to see where this is going, and how much further it might have to go.

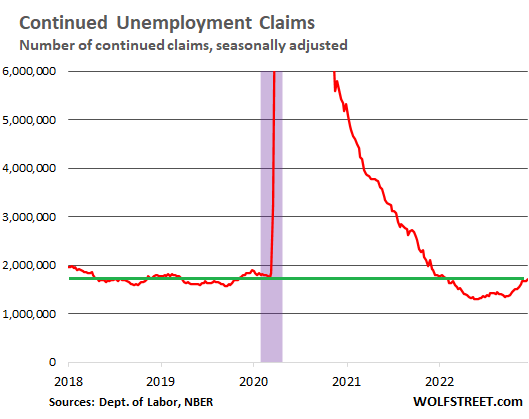

The number of people who are still claiming unemployment insurance at least one week after the initial application – these are people who haven’t yet found another job – rose to 1.71 million, according to the Labor Department today. This is not based on surveys, but on actual applications for unemployment money by people who’ve lost their jobs.

This is still historically low, in the same range as during the hot labor market in the two years just before the pandemic. But it has come off the all-time lows in June, and has zig-zagged up since then, indicating that the trend lower has now reversed and is heading higher, that the labor market is getting a little less tight, and that some of the laid-off people are now having to look longer to find a new job.

For a historical perspective, today’s reading of 1.71 million continued unemployment claims is lower than any time in the decades between 2018 and 1974.

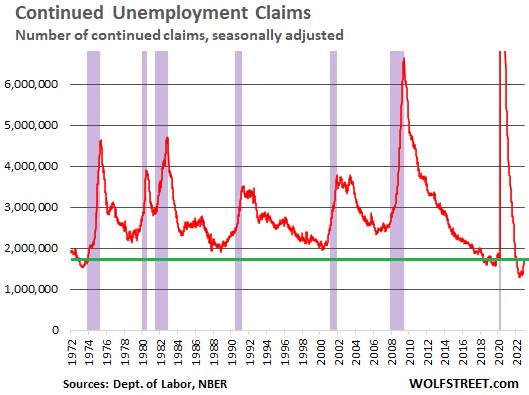

Recessions from the Great Recession back through the Double-Dip recession in the early 1980s began when continued unemployment claims spiked through about the 2.5-million mark:

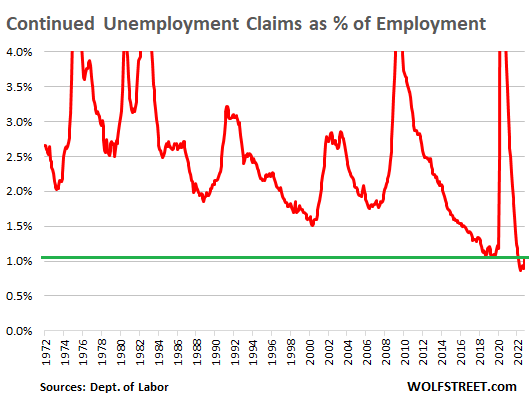

But wait… compared to total employment.

These are absolute numbers, meaning not in relationship to the number of employees on nonfarm payrolls. In percentage terms: In early 1973, there were about 76 million employees, according to payroll data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Today, there are about 153 million employees, more than double.

So continued unemployment claims back in early 1973, at the best moment, amounted to 2.0% of the number of employees – far higher than today. Today, continued unemployment claims are at just 1.1% of the number of employees.

Continued claims as a percent of the number of employees on payrolls remain at historic lows, despite the small uptick. So we’re not seeing the great loosening of the labor market just yet:

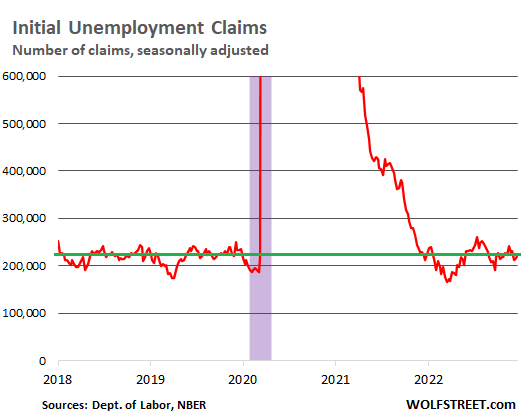

Initial claims for unemployment insurance.

Initial claims for unemployment insurance, at 225,000 in the week through Saturday according to the Labor Department today, have been in the same range since June, and in the same low range as before the pandemic.

Compared to the two years before the pandemic, the pattern of ups and downs looks very similar. It just isn’t moving much. Nothing has happened yet to change the pattern.

This is an indication that a lot of the tech employees who got laid off found a job within the period of their severance pay and didn’t need to file for unemployment compensation.

The long-term chart below shows just how low this figure of 225,000 initial unemployment claims really is, especially considering that these are absolute numbers, meaning not in relationship to the number of employees.

For the labor market to soften a little bit, we would have to see the number of initial unemployment claims rise above the 300,000-mark. And to soften meaning fully, claims may have to go above the 350,000-mark.

The Great Recession began when the number of initial weekly claims spiked through the 350,000 range. But the recessions before 2008 began when unemployment claims spiked through the 400,000-mark (except the oil-shock recession from late 1973 into 1974).

But layoffs of H-1B visa holders don’t show up here.

When H-1B visa holders get laid off, they don’t qualify for unemployment insurance, and so they don’t show up in the unemployment insurance claims data here.

But they make up a substantial portion of the staffing at many tech and social media companies, and at companies with tech divisions, and they’re part of the people who got laid off.

If they get laid off, they have 60 days after their employment to find another employer. If they cannot find another employer that will sponsor them, they’re considered “out of status” and in theory would have to leave the US.

So when they get laid off in large numbers, the weekly unemployment claims data here doesn’t capture those layoffs, and they could be substantial in number, and could be another reason the claims data hasn’t ticked up further.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()

[ad_2]

Source link