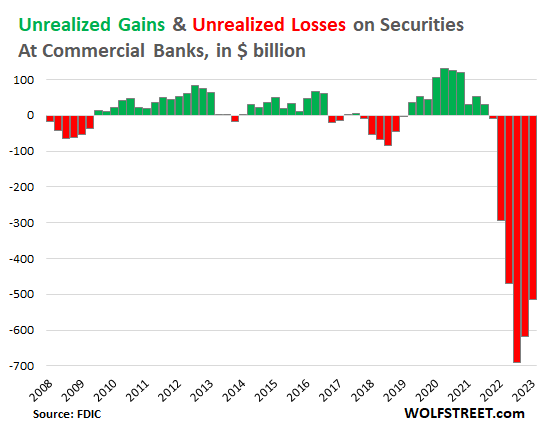

Banks’ Unrealized Losses on Securities Drop for Second Quarter in a Row, -25% from Peak

From huge to somewhat less huge? Because they’re still six times the magnitude of the prior worst-record in 2018

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

“Unrealized losses” on securities – mostly Treasury securities and government-guaranteed mortgage-backed securities – held by all FDIC-insured commercial banks in Q1 fell by $102 billion from the prior quarter, to $516 billion. This is a cumulative loss over time on all securities from the purchase, and not an additional loss incurred in the quarter.

It was the second quarter in a row of declines: They have now dropped by $174 billion, or by 25%, from the peak in Q3 2022, when unrealized losses had hit $690 billion, according to FDIC data on bank balance sheets released on Wednesday. In other words, unrealized losses are still huge, they’re still six times the magnitude of the prior worst-record in 2018, when the Fed also hiked rates. But they’re 25% less huge than they had been.

The bank collapses since March this year in the US – Silvergate Capital, Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and First Republic – all involved lightning-fast and record-huge bank runs by electronic means, that were triggered by sudden concerns about those banks’ “unrealized losses” on their securities. The chart shows “unrealized gains” in green and “unrealized losses” in red.

These unrealized losses of $516 billion in Q1 were spread over two categories of bank accounting treatments:

- Unrealized losses on held-to-maturity securities: $284 billion

- Unrealized losses on available-for-sale securities: $232 billion.

The six quarters of unrealized losses during this rate-hike cycle follow 10 quarters in a row of unrealized gains during the Fed’s pandemic-era QE and rate cuts.

When the banks collapsed, the issue wasn’t credit, such as defaulting loans due to imploding real estate prices and a tsunami of foreclosures, or defaulting corporate loans, as during the Financial Crisis.

Instead, the issue was a huge pile of pristine long-term Treasury securities and government-guaranteed mortgage-backed securities that lost market value due to higher interest rates.

As these bonds approach maturity, their market value returns to face value because face value is what the holder will ultimately get paid when the bond matures, or every time pass-through principal payments are made to MBS holders. This is the rationalization for allowing banks, under the “held-to-maturity” accounting treatment, to not “mark to market” those securities that they don’t trade.

So bank income statements look good because they don’t show the market losses on their vast securities portfolio. But they have to disclose these losses as “unrealized losses” on their balance sheets. And that turned out to be a problem too…

When uninsured depositors – who never ever look at bank balance sheets – got wind of these huge unrealized losses suddenly via media reports and social media posts, they got spooked and yanked their money out, causing the banks to collapse because they could not come up with the cash to fund the withdrawals because they could not sell those securities for prices anywhere near what they had valued them on their balance sheets, and because they didn’t have enough capital to eat those losses and live through it.

So now we keep an eye on banks’ unrealized losses because they’re one of the weak points in the financial system.

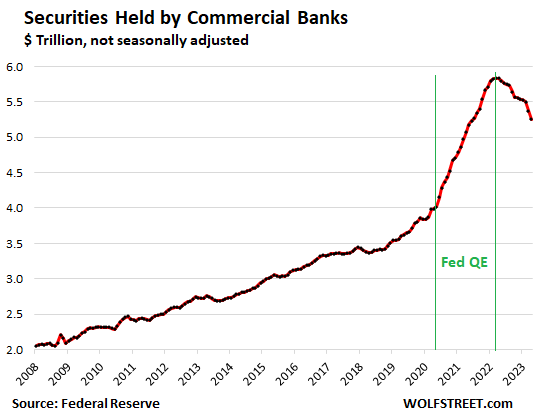

The total balance of securities held by all commercial banks – mostly Treasury securities and government guaranteed MBS – declined by $582 billion, or by 10%, to $5.25 trillion in April, 2023, from the peak in March 2022 ($5.83 trillion), according to monthly data by the Federal Reserve on bank balance sheets.

In the chart, you can see the big drops in March (-$130 billion) and April (-$120 billion). The drops were in part due to the bank failures, when some of their securities were transferred to the FDIC, rather than to other banks. The FDIC is now selling those securities to investors, and those securities have come off the bank balance sheets. Securities from failed banks that were sold to other banks remain in this total balance, but their losses were wiped out as the banks bought them from the FDIC at somewhere near current market value.

In the chart, you can also see how banks gorged on these securities as a result of the mindboggling money-printing by the Fed starting in March 2020 through early 2022, which had the effect of repressing long-term interest rates.

By August 2020, the 10-year Treasury yield had dropped to 0.5%, and banks – these morons! – were buying those long-dated securities with ultra-low yields, either not thinking at all, or thinking that yields would turn negative. And when yields began to rise in September 2020, they didn’t take it seriously, and continued to gorge on long-dated securities. And when the Fed started talking about rate hikes and ending QE in the fall of 2021, the banks still didn’t take it seriously, and it wasn’t until March 2022, after the initial lift-off rate hike, that the banks — some banks — timidly began reducing their massive holdings of now overpriced securities.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()

[ad_2]

Source link