Powell Caught in One Heck of a Squeeze: D, All of the Above is Also Possible

Debt has a nasty habit of ruling the financial world of any entity, whether it’s a household, business or nation.

By Craig Francis.

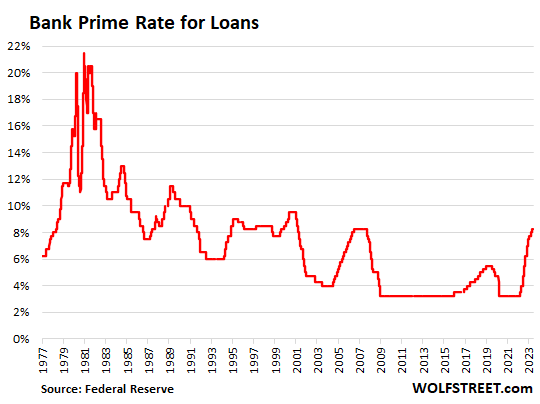

My opinions may not be shared by others, but since I’ve been through four major financial crises, including the wretched stagflationary period of 1976 to 1982 during which bank “prime rate” for loans hit 21%, these events helped me form a few opinions along the way.

In May 2023, Jerome Powell, president of the Federal Reserve, increased the Fed Funds rate for the 10th time, adding another 25 basis points to Fed fund rates. This brought the prime rate to 8.25 %, the highest in almost 20 years. This round of rate increases is the most rapid in 40 years, reflective of the Fed’s slow realization that inflation was real and tangible and not transitory as first thought.

From this point in the second quarter 2023 and going forward, I’m fairly certain we’ll see another 25-basis-point increase within a month or two, barring some unexpected event that causes Powell to pause in his plans for higher rates.

A dramatic decline in the present inflation rate or wide recognition of a strong recession could provide reasons for Powell to stop. Either event might even incline Powell to reverse course and drop rates quickly. The 2024 presidential election cycle is another event that generally produces lower rates, pump priming, and heightened monetary stimulus, as Federal Reserve Presidents often succumb to political pressure. Powell’s been pretty much flinch-proof lately, but that could change quickly if historical Fed actions are any guide looking forward.

With a recent CPI print at 5% Powell may still be compelled to increase rates another tick or two to put the final kibosh on inflation. Other factors might have him pause as he reflects on the damage that has been done by 10 rate hikes in the last 17 months. Damage is evident pretty much everywhere we look, not least of which are the financial conditions of most small and mid-sized banks and unsteady commercial real estate values.

A couple of small rate hikes over the rest of the year might help staunch inflation, yet consequences could easily turn out to be grave, including a serious recession, a big stock market air pocket, further damage to the lending sector or deleterious effects on real estate values. D, all of the above is also possible.

That means Powell is still in a tough spot as to whether he should hike again, pause for a period of time, or turn rates back down. If he continues pressing rates upwards through 2023 before a nominal pivot sometime in late 2023 or at least by early 2024, this will further exacerbate American economic conditions with effects felt worldwide. It’s a well-accepted fact that things are breaking now as a direct result of the fastest rate hike in US history.

What’ll break first? The economy, or Powell’s will to beat inflation? Looking back to the 1980-1982 period, Paul Volker, the former President of the Fed, did pause and pivot, only to see inflation spike again coupled with two back-to-back recessions. He quickly reversed course by going back to rate hikes which finally did the job of breaking the back of inflation in 1982-84 period.

As Powell reads his monetary history, he is caught in a heck of a squeeze; bump the prime rate to 8.5% within the calendar year of 2023, maybe giving one or two final rate shots to quell inflation as he floors the rate pedal to assure himself that he doesn’t make the same mistake as Volker who let off on rates before inflation was well and truly dead.

This pathway might tamp down inflation in the long term but it’ll add to the cost of living and doing business going forward. Interest is, by its nature, an inflationary cost. It’s passed down through cost chains and affects all expense factors whether loans are present or not. Even if rates stabilize at these higher levels, it leaves us with a substantial increase in the US debt. As all government costs galloped higher, the interest paid on $32 trillion in Federal debt also rose rapidly.

A $2 trillion here, a $2 trillion there, and pretty soon we’re talking about real money. In federal debt terms, as we move to the end of 2023, we’ll see another $2 trillion in debt. Moving through the federal fiscal period of 2024 and into 2025 we’ll see a minimum of another $2 trillion in US debt, notwithstanding monetary pump priming in the Presidential election cycle.

The debt ceiling resolution didn’t provide for any type of substantive spending cap. We could easily see even more deficit spending which, in and of itself, is grossly inflationary. Federal debt is one of the largest heads of the inflation Hydra, and thus it’s very hard to kill. It’ll make its presence known in all debt markets as Federal spending pushes out other investments that require loans to function.

This rapid ramp up of US debt is a big negative to the US credit rating, even while it weighs heavily on access to all capital. But it’s made worse when interest costs are added to these gargantuan totals. Half the Federal deficit is now interest on the debt. The annual borrowing cost is $1 trillion. In reality, the US treasury is financing the interest charges by tacking it on to the federal debt instead of being paid as we go.

The need to fund excess government spending, including the interest on this debt, puts strong pressure on interest rates. The US Treasury needs someone to buy this debt. While Uncle Sam is on the hook for this debt, he’s still paying the interest. But creditors will demand good rates, or they’ll seek investments elsewhere.

As the interest on the federal debt exceeds $1 trillion a year, total national debt will hit $36 trillion in two years. It’s well on its path to $50 trillion by 2030. There comes a point in time, as Powell contemplates rate policies, that most of his decisions are rendered moot. He’ll simply have lost control

As debt-based inflation takes root and we see only more red ink as the US debt moves upwards at an exponential rate, higher rates can take a life of their own. Almost all countries in which debt to GDP exceeds 100%, debt and rates tend to run past all forms of policies and human control.

For what it’s worth, rates will most likely come back down to earth for a while but not before much more damage is done. Debt has a nasty habit of ruling the financial world of any entity whether it’s a household, business or nation. Long gone is the day when US debt was manageable. With a US debt to GDP ratio of 1.30 to 1, that Roman river was crossed around 20 years ago. By Craig Francis.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()

[ad_2]

Source link